Benito Makes Us Feel Celebrated

Puerto Rico, the Caribbean, and Latin America: Bad Bunny and the power of being seen.

Si quieres leer esta edición en tu idioma, suscríbete al canal de WhatsApp de LatAm Explained en español.

This is mostly a political newsletter. I analyze elections, institutions, democracies, and regional tensions. I also discuss culture—music, film, literature—but usually to help you better understand our region. What we witnessed at the Super Bowl halftime show, though, is a perfect match of both.

Politics and culture are completely intertwined, inseparable, speaking to each other in ways that matter deeply to Latin America and Puerto Rico.

I first heard Bad Bunny in 2016. Latin trap was becoming big, and Bryant Myers was the undisputed king at that moment. I was at my university in Caracas, sitting on the floor of Módulo 6 (people who went to Andrés Bello Catholic University will know what I mean), having lunch with classmates, when one of them mentioned Bad Bunny and played “Diles.”

After that, his music became a constant part of my life. It’s wild to think we almost grew up together; he’s only three years older than me. It’s even more surprising that the artist I listened to at house parties as a teenager is now the most-streamed musician in the world and performing at the Super Bowl.

So when I was watching the Super Bowl halftime at a bar here in Prague, and I was the only Spanish speaker in the whole crowd, and every single element of the show was in Spanish, it felt like such a vindication. Like, that was for us. I don’t think I’d ever experienced anything like it before.

Watching these intrinsically Hispanic Caribbean scenes—the coconut seller, the old men playing dominoes, the kid sleeping in chairs at a wedding party—that happen not only in Puerto Rico but also in the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Cuba, Colombia, and beyond, felt like the world was being exposed to our culture. Not just Puerto Rican culture, but the broader Caribbean experience we all share. Those small, everyday moments that make us who we are were suddenly projected onto the world.

At a time of intense polarization, when the Trump administration threatened to send ICE to the Super Bowl, and conservative pundits complained the show was “too Latino,” Benito answered with love, unity, and beauty.

Aside from the obvious differences, he’s cementing his status as a modern Caribbean John Lennon, using his platform to celebrate culture, honor struggle, and insist that love and dignity can coexist with political resistance. At a time when every cultural moment becomes a battleground, and every symbol gets weaponized, Benito chose to make art that was unapologetically political but fundamentally about connection.

For years, Latin artists who wanted mainstream success in the United States had to sing in English, soften their identity, and make themselves more acceptable. Even Ricky Martin, who has represented Puerto Rico and Latinos worldwide for decades and sang “La Copa de la Vida” for the 1998 World Cup (the best World Cup song ever, in my opinion), performed it in English at the Grammys that year. Nearly 30 years later, he returned to the global stage to perform with Bad Bunny, this time entirely in Spanish. That change says it all.

Bad Bunny refused to code-switch. He appeared fully and unapologetically Puerto Rican and made 135 million people meet him on his terms. He invited, not argued. He celebrated, not confronted.

This is important for Puerto Rico because the island exists in a strange colonial limbo. Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens who can’t vote for president. They live under U.S. laws but have no voting representation in Congress. The island’s infrastructure has been neglected for decades. The power grid fails often, recovery from Hurricane Maria took years, and gentrification is forcing locals out as wealthy Americans buy property without paying taxes.

Bad Bunny’s performance spoke to all of this, but with artistry instead of aggression. When dancers climbed electric poles that sparked, it referenced “El Apagón” (The Blackout), his song protesting Puerto Rico’s constant power outages and the colonial neglect behind them. The music video shows real scenes of Puerto Ricans living without electricity, waiting in line for ice, and cooking by candlelight. On the Super Bowl stage, Bad Bunny turned that suffering into art and made a statement: this is our reality, and you will see it.

The performance of “Lo Que Le Pasó a Hawai’i” was a strong message. The song is a bolero, a slow and romantic style, but its lyrics are a warning. It tells how Hawaii was annexed by the United States, how native Hawaiians lost their land and culture, and how it became just another American state. “I don’t want them to do to you what they did to Hawai’i,” the song says. Ricky Martin performed a gentle, beautiful melody about resisting statehood and cultural erasure on American television, in Spanish, with a message of unity and caution.

The symbolism kept growing. Bad Bunny held up the Puerto Rican flag with the light-blue triangle, which is linked to the pro-independence movement and was once illegal to display under U.S.-appointed governors. He shouted “God bless America” and then named every country in the Americas, from Chile to Canada, as performers ran out with each nation’s flag. He was reclaiming a word that the United States has claimed for itself. We are America, too. Our stories matter. Our languages matter.

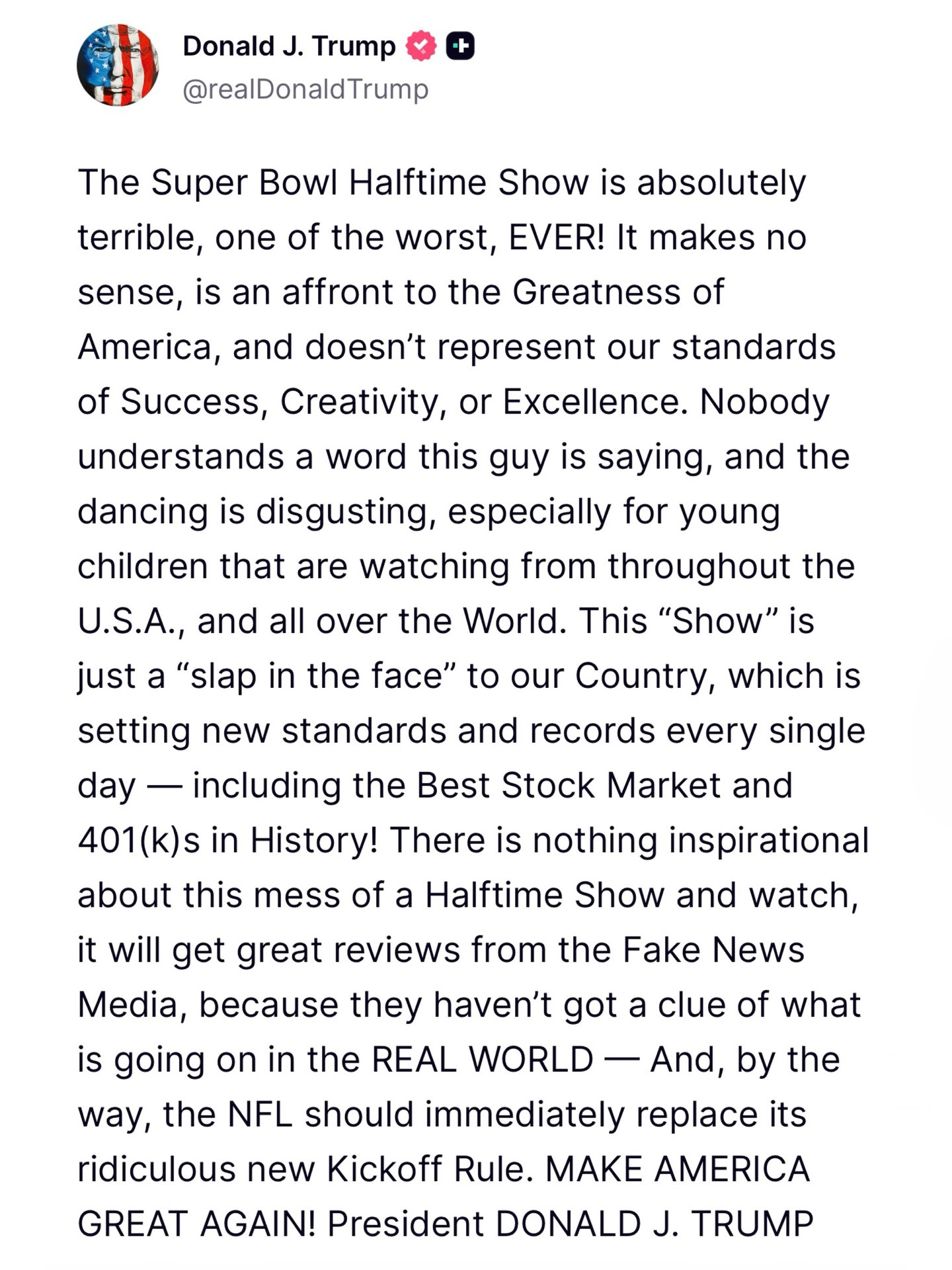

Minutes after the performance, Trump posted on Truth Social. The message was clear. To Trump and his supporters, an all-Spanish performance celebrating Puerto Rican and Latin American culture isn’t “American” enough.

Benito wasn’t performing for Trump’s approval. He was performing for us, for Puerto Ricans, for Latinos, and for anyone who’s been told their language doesn’t belong, their culture isn’t valuable, or their identity needs to be changed for mainstream acceptance.

For the rest of Latin America, Bad Bunny stands for something just as powerful: the chance to succeed globally without fitting into Anglo expectations. We don’t have to speak in English, explain ourselves, or ask permission to take up space. We can do it with messages of love and unity, not by copying the anger and division around us.

It’s a bit ironic, since I’m writing this in English. But you understand what I mean.

Bad Bunny makes us feel celebrated, and I notice that effect wherever I go. It’s more than pride; it’s vindication. It feels like we don’t have to change to be seen. Our cultures, languages, struggles, and joy all deserve to be on the world’s biggest stages. We can be political without bitterness. We can resist and still choose love.

He has used his platform, sometimes taking more radical stances in the past, to deliver a beautiful, heartfelt, artistic show about love and unity while still making strong political statements. That’s the balance we need. In a world that pushes us to choose sides and stay angry, Benito showed a different path. You might not like his music, but he is a strong representative for us.

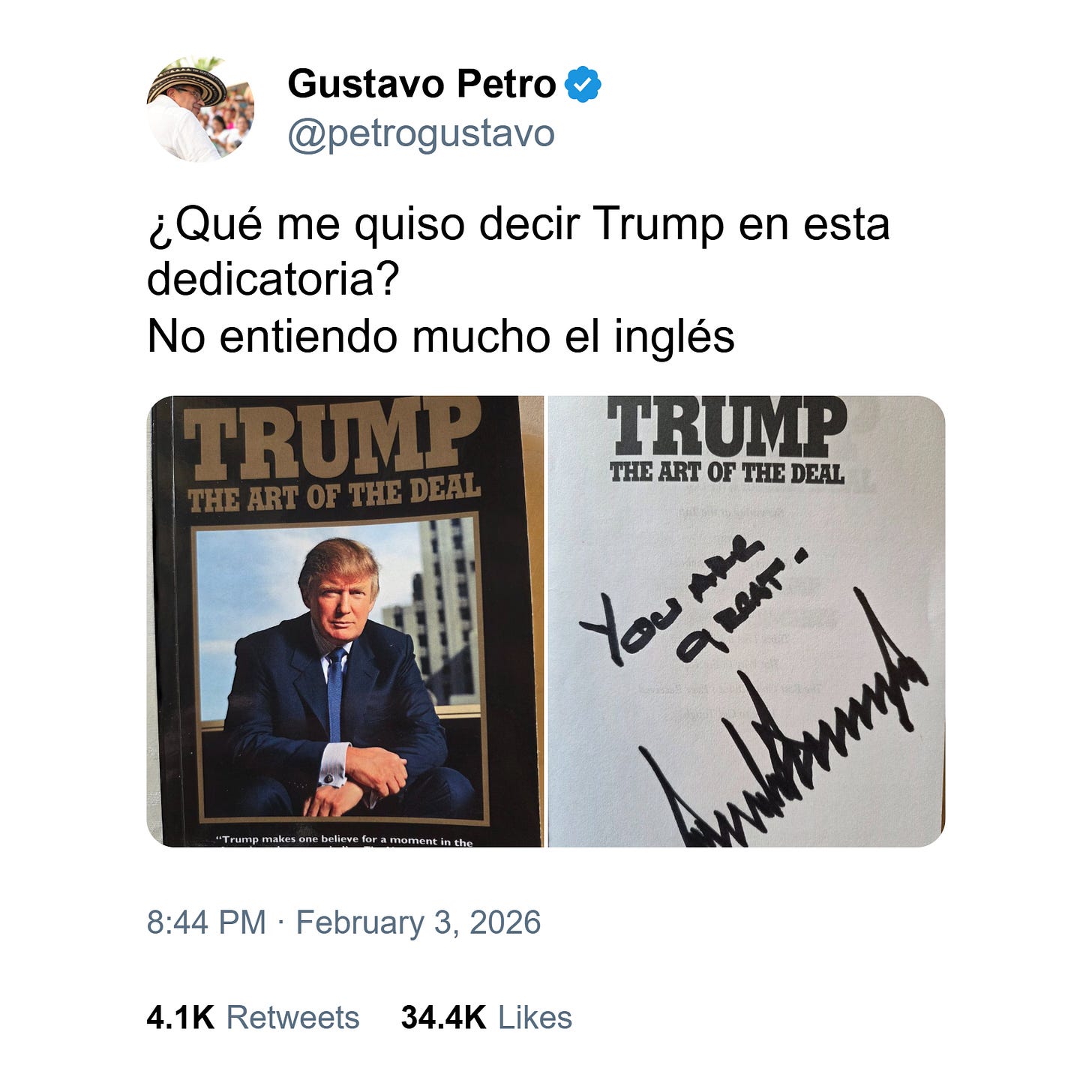

Petro Meets Trump at the White House

Colombian President Gustavo Petro went to Washington on February 3 for his first in-person meeting with U.S. President Donald Trump. The two met in the Oval Office for two hours, and the conversation was friendlier than expected, given their past. Trump had previously called Petro an “illegal drug leader” and even talked about possible military action against Colombia. Petro had criticized Trump’s policies as “war crimes” and described the U.S. raid that captured Venezuela’s Maduro as a “brutal imperial aggression.”

At the White House, though, they got along. Trump said, “We worked on it,” referring to their cooperation on fighting drugs. Petro asked for help catching drug traffickers and even wanted Trump to help solve Colombia’s dispute with Ecuador. Trump also gave Petro a handwritten note that said, “Gustavo – A great honor – I love Colombia.”

It almost seems like Petro wanted to check this meeting off his list before leaving office. Jokes aside, it’s obviously a positive sign that the U.S. and Colombia have eased tensions. Still, remember that Petro’s term is ending soon, as Colombia will hold presidential elections later this year.

Bolivia: Paz Approaches His First 100 Days

Rodrigo Paz is approaching his first 100 days as Bolivia’s president, and we can start thinking about the balance. After decades of socialist MAS party rule, Bolivia has its first center-right president since 2006. He inherited the worst economic crisis in four decades—20% inflation, critically low foreign reserves, fuel shortages, and lines at gas stations.

He responded boldly by ending government fuel subsidies, which had been costing $10 million a day. Fuel prices more than doubled overnight. The country erupted in general strikes and road blockades, and cities were paralyzed for almost a month. Earlier Bolivian presidents had given in under this kind of pressure.

But Paz stood his ground on the subsidy cuts and showed flexibility in other areas. He raised the minimum wage by 20%, increased pensions, and added cash transfers for the poorest. After weeks of a standoff, he reached a compromise that kept the subsidy cuts but dropped the controversial fast-track investment rules. The strikes then faded.

Meanwhile, Evo Morales, Bolivia’s former president and leader of the MAS party, has been missing for over a month. He vanished soon after he condemned the U.S. raid on Venezuela’s Maduro. His supporters claim he has dengue, but others believe he left the country to avoid an arrest warrant.

Bolivia is finally starting a new chapter. The question now is what comes next.

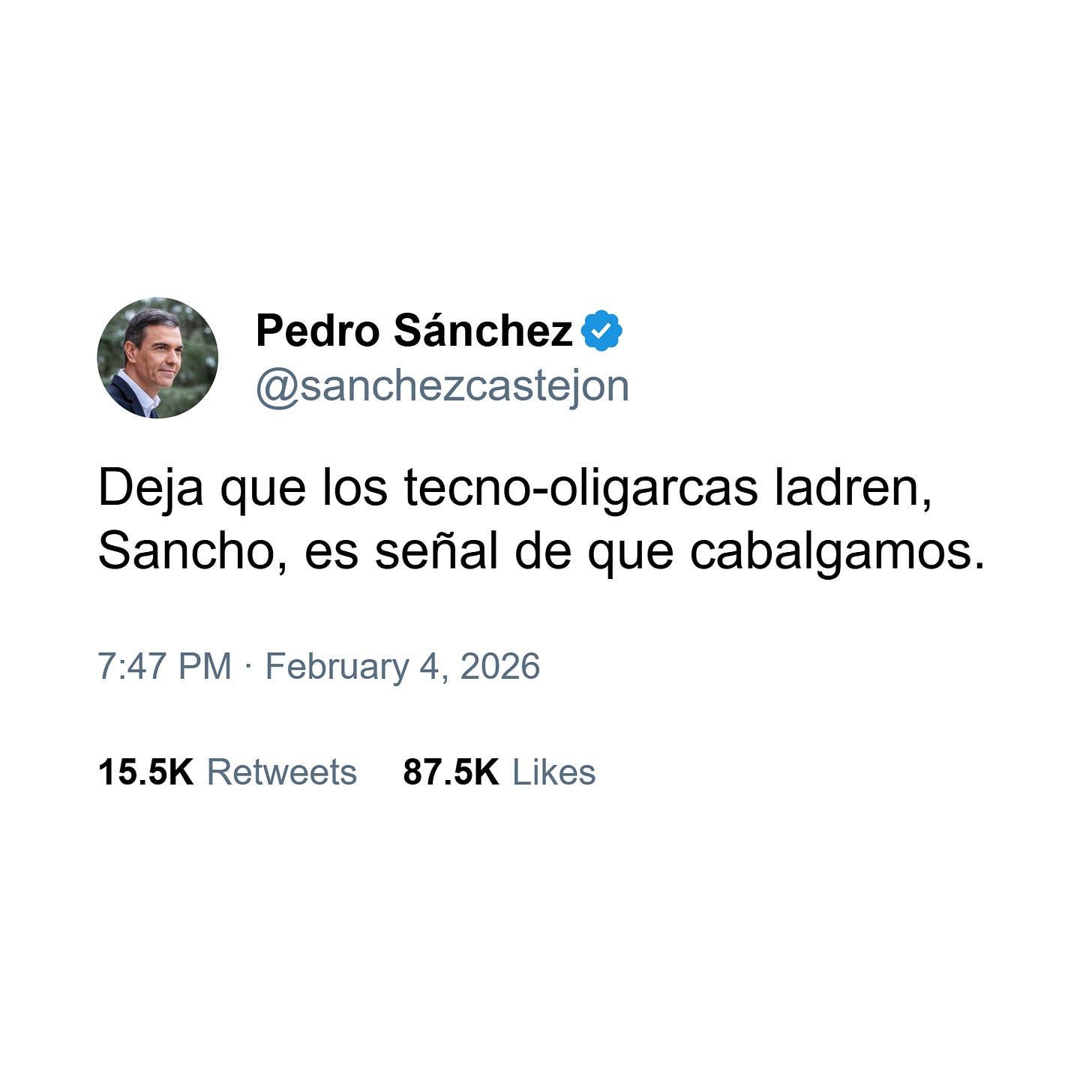

Spain: Sánchez Challenges Elon Musk

In this newsletter, we’ve talked about how our relationships with leaders in Latin America are shaped by how people in Spain relate to theirs. That might sound like an oversimplification, but it’s worth considering.

This is why it’s important to pay attention to Pedro Sánchez. On February 3, Spain’s Prime Minister announced plans to ban social media for anyone under 16 and to hold tech executives personally responsible for hate speech on their platforms. Elon Musk responded on Twitter, calling him “Dirty Sánchez” and a “tyrant.” Later, Musk called him “the true fascist totalitarian.”

At the same time, Sánchez approved a plan to grant legal status to about 500,000 undocumented immigrants in Spain. Many of these people are Latin Americans who will benefit directly.

It’s interesting how Sánchez handles crises by rallying his supporters. This time, he’s focusing on outside opponents. Musk represents Silicon Valley’s influence, and the decision to regularize migrants is framed as a humanitarian response to rising xenophobia in the West. This strategy turns opposition into motivation and critics into rallying points.

Tego Calderón and the Revolutionary El Abayarde

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl performance honored reggaeton legends like Daddy Yankee, Don Omar, Héctor El Father, and Tego Calderón. I’ll cover the others in future newsletters, but today I want to focus on the most underground of them all.

Tego Calderón was born in 1972 in Santurce, Puerto Rico, and started his career in the late ‘90s when reggaeton, then known as “underground,” was still taking shape. While many artists focused on fast beats and party themes, Tego mixed salsa, reggae, and hip-hop, blending street style with strong social messages.

His first album, El Abayarde (2002), was an experiment. People weren’t sure if this rougher, slower, and more political style of reggaeton would catch on. Well, it sold over 300,000 copies worldwide and received a Latin Grammy nomination. The album became a classic, with hits like “Pa’ Que Retozen,” “Métele Sazón,” and “Guasa Guasa.”

Tego stood out because he was proud of his Afro-Latino roots and cared deeply about social issues. While most reggaeton focused on party and romance, Tego rapped about racism, inequality, and the challenges faced by Black Puerto Ricans. Songs like “Loíza” spoke directly about racism on the island. He gave reggaeton its soul, its political voice, and its connection to real life.

The music industry often didn’t know how to handle Tego. Record labels wanted him to tone down his message, but he refused. While artists like Daddy Yankee became huge stars, Tego’s following stayed more underground and grassroots. Still, his impact is clear. Bad Bunny has even said, “Tego Calderón is the biggest in the industry.”

The Super Bowl tribute showed that without Tego’s bold move and El Abayarde’s proof that reggaeton could be deeper than party songs, artists like Bad Bunny wouldn’t have the freedom to be political and creative. Tego opened the door, and a whole generation followed.

That’s all for now. If you found this valuable, here’s how you can support me:

Subscribe for free to get editions like this every week: one main analytical piece, three important stories from Latin America, and one cultural recommendation to help you understand our region better.

Like this post by tapping the heart button. It helps more people discover LatAm Explained.

Leave a comment below. I read every single one, and your perspectives make my content better.

Share this with someone who’d appreciate clear-eyed analysis of Latin America. Forward this email, or use the button below:

You can also follow me on Instagram, X, and TikTok for more of my content.

Gracias por leer. Hasta la semana que viene.