Chileans 'Kast' Their Vote: They Turned Far-Right

The result was predictable after round one. What wasn't? Kast's surprisingly conciliatory tone since winning.

Si quieres leer esta edición en tu idioma, suscríbete al canal de WhatsApp de LatAm Explained en español.

As expected, José Antonio Kast won Chile’s presidential runoff, earning 58 percent of the vote and defeating communist candidate Jeannette Jara by a wide margin. This outcome was expected. In the first round, right-wing candidates together received almost 70 percent of the vote, making Kast the clear favorite.

Chilean politics often move in cycles. Since Michelle Bachelet was first elected in 2006, the country has switched back and forth between left- and right-leaning governments: Bachelet, then Piñera, then Bachelet again, then Piñera, then Boric, and now Kast. If this pattern continues, the left could return to power by 2030.

The main question now is not about Kast’s win, but how he will lead. During his campaign, he spoke forcefully, praised Pinochet’s rule, promised to deport many people, and said he would use the military to fight crime. At his victory rallies, supporters shouted chants for Pinochet. This caused concern for many people.

Since the results came out, he has acted in a conciliatory way. President Boric called him in a positive, publicly broadcast conversation, and Kast met with his opponent, Jara. In his victory speech, he promised to govern for all Chileans and tried to bring people together. Kast won in a divided country, with 42 percent voting against him even after crime became the main issue. If he wants to pass laws in a split Congress, he cannot pretend to have broad support.

Immigrants, especially Venezuelans and Haitians without legal papers, are most affected. During the campaign, they were blamed for various problems. Kast gained support by connecting migration to crime. He has promised to build barriers at the northern border and deport many people. Whether he can do this depends on Chile’s strong institutions. Courts can block illegal actions, Congress can refuse to fund them, and social groups can resist.

This is the main conflict to watch. Kast comes from a far-right background. His father was a member of the Nazi party, and Kast campaigned to keep Pinochet in power in 1988. He is open about his views. But Chile in 2025 is very different from 1973. Kast won a fair election and will have to govern fairly, even if he might want something else.

A bigger question is why Chileans voted this way. Crime has doubled in recent years, and the economy has stalled. Two attempts to change the constitution failed. Many voters picked Kast not because they agreed with his ideas, but because they wanted change and hoped he would restore order without hurting democracy. Boric’s mistakes made this risk possible.

What happens next depends on Kast’s first hundred days. If he focuses on crime and the economy, where he has broad support, he could govern well. But if he targets social issues that divide people or tries to take away LGBTQ rights, he will face strong resistance. We will find out after March 11, 2026, when he will take office.

Bolivia’s Arce Jailed: Is This Justice or Political Payback?

Former President Luis Arce was arrested on December 10 and put in jail before his trial for suspected corruption. The case focuses on about $52 million from a development fund he managed as economy minister, which was allegedly misused between 2006 and 2017.

After almost 20 years of Arce’s Socialist Party in power with little oversight, it is reasonable to look back at their time in office. The Fondioc scandal is real: money was diverted, fake projects were set up, and someone should be held responsible.

Still, the quick pace of these events is worrying. The case was ignored for years, but moved forward just days after the new conservative government took office. A judge soon ordered five months in jail. This timing gives critics a reason to say the law is being used for political reasons, no matter what the evidence shows.

Both things can be true: Arce may be guilty, and the prosecution could also be driven by politics.

Cuba Welcomes the US Dollar

On December 11, Cuba partially legalized the use of US dollars. Now, businesses can use foreign money, and exporters can keep up to 80 percent of their earnings in strong currencies. The regime says this will last only until the peso becomes stable.

The geopolitical context is very important here. For years, Chávez and Maduro helped keep the island afloat. While Venezuelan support is not entirely gone, it has been deeply affected by Venezuela’s own internal problems, leaving Cuba to deal with the consequences.

It’s good to see the regime making changes instead of sticking with old, failed policies. Still, Cuba’s economic problems are mostly due to years of mismanagement and rule by a small elite, not just the US embargo. They have often blamed Washington for its troubles while avoiding basic market reforms.

Partial dollarization treats a symptom, not the disease. Without addressing the fundamental dysfunction, this is just rearranging deck chairs.

Energized, Milei Targets Labor Reform

President Javier Milei sent his labor reform bill to Congress, only weeks after his coalition nearly doubled its seats in the midterm elections. The timing is intentional: just after completing two years in office, Milei is now pushing his boldest policies yet.

Labor law is at the heart of Peronism. Their political identity is built on group negotiations, strong unions, and worker protections. Milei waited for the right time to take on this issue. He avoided it during his first year, when his coalition was weaker and the economy was struggling.

The bill shifts negotiations to the company level, replaces severance pay with compensation funds, and limits strikes. Unions call it the most regressive reform since the dictatorship. From their perspective, they are right to be concerned: if Milei reduces union power, he also weakens Peronism’s main support. It will be voted on this week, along with the 2026 budget.

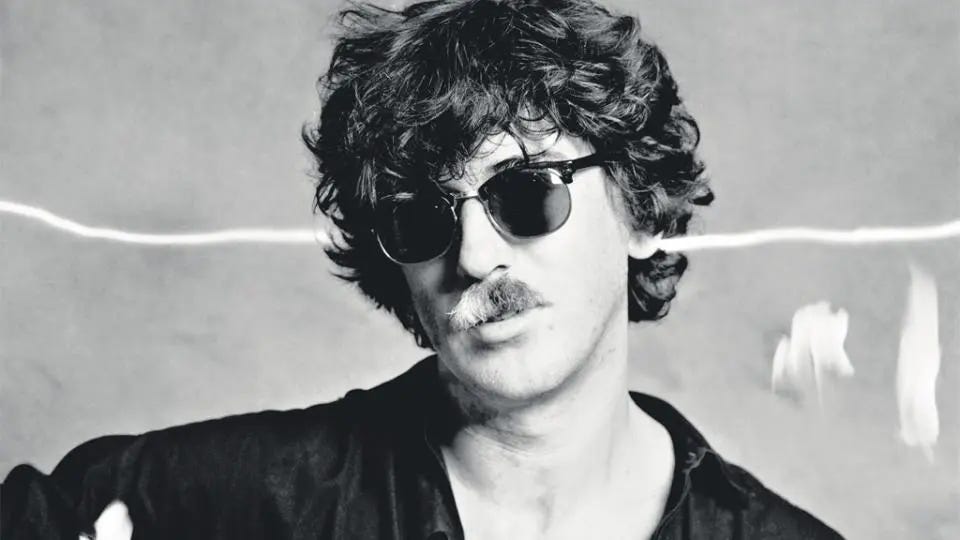

Charly García: Argentina’s Greatest Artist

On December 7, Buenos Aires unveiled “Esquina Charly García” at the corner of Santa Fe and Coronel Díaz in Palermo. The city put up a special street sign and a big ceramic mural to honor the 74-year-old rock legend. Hundreds of fans came out to celebrate.

Honestly, it’s hard to put Charly García into words. I could go on and on. People often compare him to John Lennon, David Bowie, or Elton John, but that doesn’t really do him justice.

Charly stands among the greatest artists in global music history, no question.

Charly had his own iconic styles and different phases long before Taylor Swift made that idea popular. He was already showing up on English-language media in the early 1980s, like the Today Show, way before artists like Shakira or Bad Bunny became famous worldwide.

If I had to choose two people who represent Argentina, it would be Charly and Maradona. That’s how important he is.

Charly was a child prodigy with perfect pitch. He became a rebellious figure and lived the real rockstar life, even famously jumping from a hotel window in 1991 and somehow surviving a nine-story fall.

But more than the wild stories, he openly challenged the Videla dictatorship when speaking out could be deadly. He turned resistance into art.

I always knew he was one of the greats, but I didn’t really understand his work until I lived in Argentina. That’s when I saw how he turns the spirit of Argentina into powerful melodies and lyrics. The rhythm, the local attitude, the sadness, the defiance—it’s all in his music.

He’s also a mentor to other Argentine legends like Fito Páez and Andrés Calamaro. You can hear his influence in generations of Latin American rock. His MTV Unplugged is probably his easiest album to get into, but the song that always moves me is the studio version of “Ojos de videotape.”

Naming a corner after him in Buenos Aires isn’t just about honoring a musician. It’s a way of saying that Charly García stands for Argentina through his music. And it’s absolutely deserved.

The Follow-Up

María Corina Machado reached Oslo for the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony in a dramatic way. She left Venezuela using a secret route and arrived in Norway after the ceremony had already started on December 10. Her daughter accepted the prize for her.

The head of the Norwegian Nobel Committee gave a speech that strongly criticized Maduro’s government, more so than at any previous ceremony. Presidents from Argentina, Ecuador, Panama, and Paraguay attended to show support. Machado dedicated the prize to all Venezuelans and promised to keep fighting.

Now, the main question is what will happen next. Will Machado visit other countries to put more pressure on the government? When could she return to Venezuela, especially as Trump increases military pressure on Maduro? If she returns, she risks being arrested or worse. If she stays abroad, she might lose touch with the opposition at home. The government has clearly made her a target, so every choice she makes is risky.

Meanwhile, Honduras still does not have an official result from its November 30 election. About 15 percent of the votes have not been counted because of different problems. So far, the partial results show Trump-backed Nasry Asfura from the National Party leading Salvador Nasralla from the Liberal Party by about 40,000 votes, with 40.5 percent to 39.5 percent.

The situation is getting more chaotic. The voting system has failed, and both sides are accusing each other of cheating. President Xiomara Castro says there was an “electoral coup” involving Trump. A special recount was ordered on December 12 and is expected to take several days. Both candidates have claimed victory. Protests have started, and a group in Congress is refusing to accept the results.

That’s all for this week. If you liked what you read, please subscribe.

You’ll get something like this every Monday: one main analytical piece, three important stories from Latin America, and one media suggestion to help you learn more about our region.

You can also follow me on Instagram, X, and TikTok for more.

Gracias por leer. Hasta la semana que viene.