Costa Rica Has Our Attention (And Our Concern)

Laura Fernández extends the Rodriguismo project. Will Costa Rica's institutions hold?

Si quieres leer esta edición en tu idioma, suscríbete al canal de WhatsApp de LatAm Explained en español.

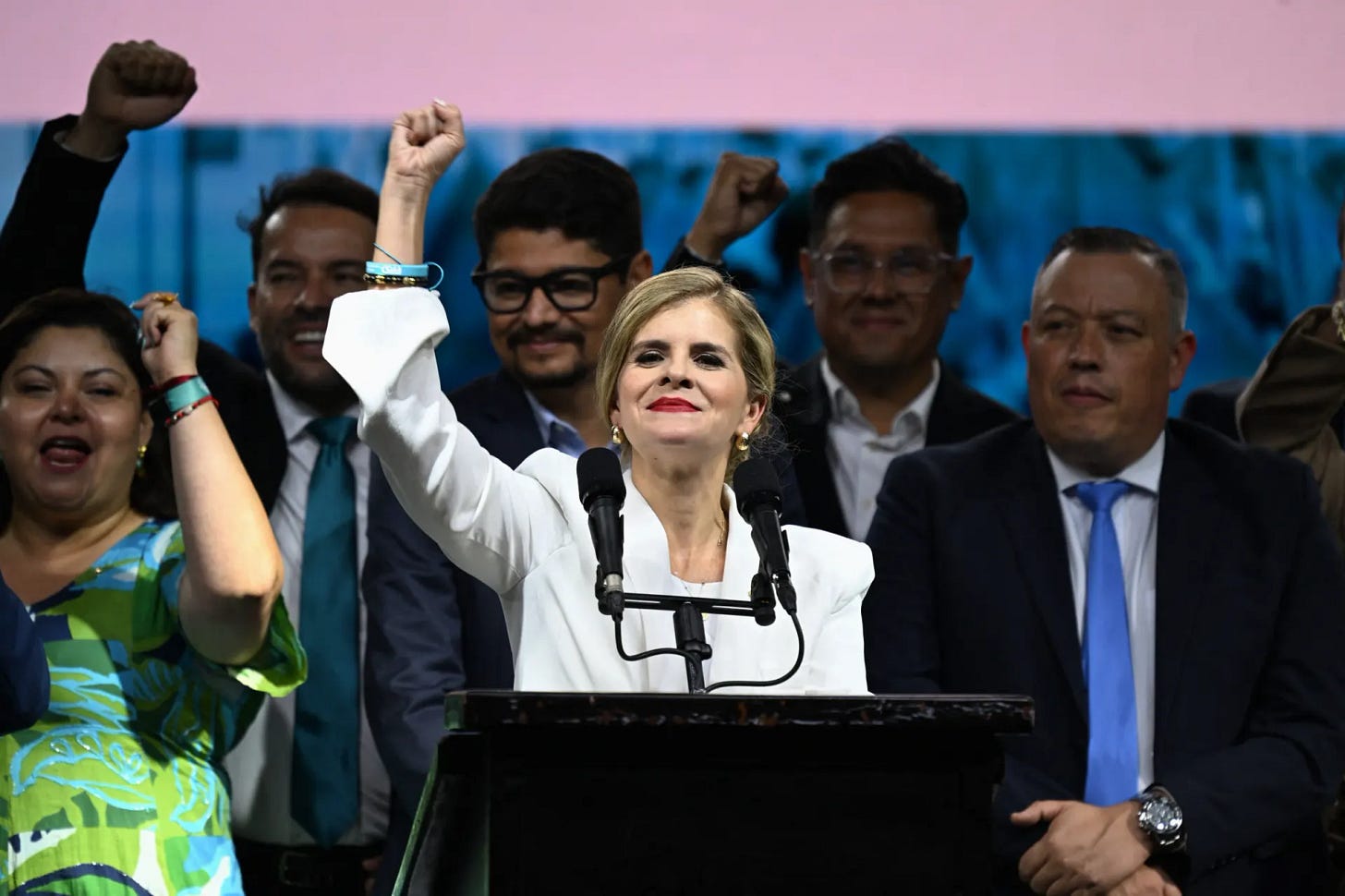

Laura Fernández won Costa Rica’s presidency in the first round on February 1st with 48.5% of the vote, easily passing the 40% needed to avoid a runoff. Her closest rival, centrist Álvaro Ramos, received 33.4%. No other candidate reached 5%. Fernández’s Sovereign People’s Party also won 30 out of 57 legislative seats. That’s a strong result, but still not enough for the supermajority required to change the constitution.

We’ve talked about outgoing President Rodrigo Chaves before in this newsletter. He’s known for clashing with institutions, surviving two failed impeachment attempts, and having a confrontational style. Fernández is his protégée—she was his chief of staff and minister—and she campaigned on continuing his approach. It’s “Rodriguismo without Rodrigo,” so to speak.

Here’s why this matters: In Latin America, Costa Rica—and maybe Uruguay—stand out as examples of strong democracies with solid institutions. When we look for countries that “do it right,” we look to Costa Rica. So when Costa Rica shows signs of trouble, the rest of us notice.

While Chaves was in office, I noticed some worrying trends: attempts to remove Supreme Court judges, efforts to allow his own re-election, extensions of emergency powers, attacks on the media, and rising insecurity even though he promised to be tough on crime. These issues aren’t disastrous yet, but they’re troubling because they’re happening in Costa Rica.

Fernández is more of a technical, less personalist politician than Chaves. She might be able to carry out his agenda more effectively, which could be positive or negative depending on what that agenda turns out to be. This situation reminds me of Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff in Brazil: the charismatic founder followed by a technocratic successor trying to make the project last. We know how that ended.

It’s also striking how similar Central America looks right now. Bukele is in charge in El Salvador, Asfura in Honduras, and now Fernández is continuing Chaves’s project in Costa Rica. Fernández’s main focus is crime—Costa Rica ended 2025 with record homicides, and voters liked her tough security message. All three governments are friendly with Trump, all three focus on hardline security, and all three are skeptical of international oversight. Chaves and Bukele are close—Bukele was the first foreign leader to congratulate Fernández. Central America seems to be moving toward a model that puts order above everything else.

But here’s what gives me hope about Costa Rica: its institutions are strong and will push back. Costa Rica got rid of its military in 1948. Its Supreme Electoral Tribunal is truly independent. The courts still work. The press is still free and outspoken. Even the fact that so many Costa Ricans are worried about Chaves and Fernández shows how strong their democracy is.

I really admire how alert Costa Ricans are. They expect a lot from their leaders. When a president clashes with the Supreme Court, Costa Ricans see it as a serious problem. In most of Latin America, people might just shrug and say, “Well, at least he’s not stealing that much.” Costa Rica’s democratic culture expects and demands more.

There’s also a practical limit: even though Chaves and Fernández have said they want to end the one-term presidential limit, they don’t have enough support in Congress to make it happen. The numbers just aren’t there.

So yes, everyone is watching Costa Rica. And yes, there’s some worry. But Costa Rica has faced tough times before, and its institutions have held up. The real question is whether they can handle another four years with a government that sees them as obstacles instead of safeguards. For the region’s sake, I hope they can. We need Costa Rica to remain Costa Rica.

Kast Visits Bukele’s Prison

We’re not done mentioning Bukele. What a guy. Just when you think he’s reached peak regional influence, Chile’s President-elect José Antonio Kast shows up at his doorstep.

On January 30th, Kast visited El Salvador’s well-known CECOT mega-prison, the “Terrorism Confinement Center,” where tens of thousands of accused gang members are held under Bukele’s state of emergency. He arrived with security ministers by helicopter, toured the cellblocks, and praised El Salvador’s approach. “We need to import good ideas and proposals to combat organized crime,” he said.

Kast has talked about mass deportations as part of his campaign. With Trump now sending migrants to El Salvador’s prisons and Kast showing clear admiration for Bukele’s model, it wouldn’t be surprising if he considers something similar. Still, Chile’s institutions and legal system are much stronger than those in Central America.

These weeks before Kast’s March inauguration can tell us a lot about his priorities. He’s a career politician in a strong democratic system, not a Bukele-style disruptor. But if he’s spending his transition period touring Bukele’s prisons and studying his methods, that signals where his focus will be.

The question is how he’ll adapt these ideas to Chile’s very different institutional reality.

Honduras: Asfura Takes Office

The presidential election in Honduras has finally ended. Nasry “Tito” Asfura became president on January 27 after winning by about 26,000 votes against centrist Salvador Nasralla. The race was extremely close, with loud fraud accusations and a vote count that took weeks. Still, the electoral tribunal confirmed Asfura’s win in mid-January, and the transition went ahead.

It’s a good sign that Asfura focused on unity in his inaugural speech. “The elections are over, now we must govern for all Hondurans,” he said. After months of chaos and division, a call for national unity is just what Honduras needs. Whether he can keep that promise is uncertain, but at least his message is encouraging.

Asfura has decided to take on the role of Health Minister himself. He chose not to appoint anyone to the position and will oversee the ministry directly, with support from new health sector deputies. This is unusual, since presidents rarely manage ministries themselves. It shows he is serious about tackling Honduras’ healthcare crisis, which includes hospital strikes over unpaid wages and major shortages of medical supplies. Time will tell if this direct approach helps or simply gives the president too much control.

Trump Doubles Down on Cuba

I’m not certain whether Cuba’s regime will collapse or, more likely, start collaborating with the Trump administration in a similar fashion to what we’re seeing with Delcy Rodríguez in Venezuela. But I do know something has to give.

Cuba has faced tough crises before. The Special Period in the 1990s, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, is a good example. But back then, the Castros were in charge, and Cuba always had the support of a major ally—first the USSR, then Venezuela. Now, both sources of support are gone. Maduro’s capture ended Cuba’s oil supply, and the U.S. is determined to block any new help.

Trump threatened tariffs on any country that supplies oil to Cuba, and it’s having an effect. Venezuela stopped sending oil. Mexico quietly paused its deliveries because of U.S. pressure, and Sheinbaum’s government will not risk its own interests to help Díaz-Canel. Within three weeks, Havana faced severe fuel shortages. The Cuban peso lost over 10% of its value in January. Blackouts in the capital now last up to 10 hours.

This is not the Special Period. It could be even worse. Cuba is being cut off economically, and there is no one left to help. The country is running out of options fast.

Carlos Santana and the Supernatural Phenomenon

Bad Bunny stunned the world this week when he was awarded the Grammy for Album of the Year for Debí Tirar Más Fotos. I kept seeing in the press that it was the first Spanish-language album to win that category, so I got curious and started looking for his predecessors. Who came closest?

Carlos Santana is the closest example, thanks to his 1999 album Supernatural. It won Album of the Year and eight other Grammys, tying Michael Jackson’s Thriller for the most Grammys won by a single album.

So let’s talk about Santana.

I still remember a tough loss from college. My friends and I nailed “Somebody to Love” by Queen at a karaoke contest. We got the harmonies right, hit all the notes, and really brought the energy. But we lost to a guy in a leather jacket who sang “Smooth” from this album. I’m still a bit salty about it.

Back to Santana: it’s wild to remember he played at Woodstock in 1969. His performance of “Soul Sacrifice” is legendary. He was only 22, yet he delivered one of the festival’s most iconic moments. That was 30 years before Supernatural brought his music to a new generation and revived his career.

Supernatural was a huge success, selling over 30 million copies worldwide. Collaborations with Rob Thomas (”Smooth”), Wyclef Jean (”Maria Maria”), and Maná (”Corazón Espinado”) helped connect Latin rock with mainstream pop.

If you want to understand Santana’s legacy, listen to Abraxas from 1970. It’s probably his most important album. My colleagues from the Los 600 Discos de Latinoamérica project rank it as the 52nd best Latin American album ever. Abraxas is where Santana perfected his mix of rock, blues, and Afro-Cuban rhythms, which became the base for all his later work.

That’s all for now. If you found this valuable, here’s how you can support this work:

Subscribe (it's free!) to get editions like this every week: one main analytical piece, three important stories from Latin America, and one cultural recommendation to help you understand our region better.

Like this post by tapping the heart button—it helps more people discover LatAm Explained.

Leave a comment below. I read every single one, and your perspectives make this newsletter better.

Share this with someone who’d appreciate clear-eyed analysis of Latin America. Forward this email, or use the button below:

You can also follow me on Instagram, X, and TikTok for more of my content.

Gracias por leer. Hasta la semana que viene.