Cuba Has No Friends Left. What's Next?

The regime survived the Special Period. This time, it looks different.

🇪🇸 Si quieres leer esta edición en tu idioma, suscríbete al canal de WhatsApp de LatAm Explained en español.

The other day, I was at a table with a few people from the U.S. and other international people, and the topic of Cuba came up. No one seemed to make the connection between Cuba and Venezuela. We in Latin America are so aware of it that we forget some other countries might not understand how deep this goes.

To put it simply, there are three dictatorships in Latin America: Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela. (A fourth one is starting to form, and if you read this newsletter, you probably know which one I mean). These regimes have supported each other and worked together for years. Of the three, Nicaragua is probably the most repressive and brutal, which is saying a lot, but it gets the least attention.

When the U.S. invaded Venezuela and removed Maduro on January 3rd, the effort was led by U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who is Cuban American. It was easy to guess he might eventually turn his attention to Cuba (or that Venezuela was a necessary step for him to take before going after the Cuban regime), and that is what’s happening now.

For the past twenty years, Cuba has received millions in oil and aid from Venezuela, enough to rebuild its electrical grid and modernize basic infrastructure several times. But the regime used those resources to keep its hold on power instead of helping ordinary Cubans. Now, that support is gone. Venezuela stopped shipments after Maduro was captured, and Mexico stopped Pemex deliveries on January 27th because of pressure from Washington, which is blocking shipments and warning them not to help Havana. Russia sent only two tankers in all of 2025 and is not making up the difference. Cuba needs about 100,000 barrels of oil a day, but produces only 32,000 to 40,000.

The humanitarian crisis is severe. On February 13th, the power shortage reached over 1,700 megawatts. Blackouts now affect 60% of the country during peak hours, and some areas have outages lasting more than 20 hours. Since February 10th, jet fuel has been suspended at all nine international airports, so airlines have had to cancel flights. The government declared a national emergency on February 6th and put measures in place: a four-day workweek, gasoline rationed to about 5.25 gallons (paid in dollars only), and hospital services limited to urgent care.

For more than sixty years, the Cuban people have lived under similar circumstances. Even during the hardest times, like the Special Period in the 1990s, Cuba’s leaders managed to stay in power because they controlled all sources of information. Back then, there was no internet or social media; all media was tightly controlled by the state, and dissent was much easier to silence. Yet despite decades of embargo, the island always found a lifeline, first from the USSR, then from Venezuela.

What’s different now is that the regime can’t control the narrative as before. With the internet and social media, information spreads quickly, and Cubans can see and share what’s happening around them in real time. The government’s grip is still strong, but it’s no longer absolute.

According to Polymarket, bettors assign a 34% chance that Miguel Díaz-Canel will leave the presidency by the end of the first half of this year.

If the U.S. attacks Cuba or the regime falls on its own, you don’t need to apologize to the Cuban people. Feel sorry for what people will face in the coming months, but don’t regret it if the Cuban Communist Party collapses.

My mom is a big fan of the Cuban salsa singer Willy Chirino, so I grew up listening to him. He hasn’t been able to return to Cuba since 1961 because of his criticism and his songs about the Cuban situation and the suffering of its people. He has a song called “Nuestro Día Ya Viene Llegando” (Our Day Is Coming), where he tells his story of leaving Cuba as a child and promises that his people will celebrate soon.

That song came out in 1991. Maybe he will finally get to sing it in Havana 35 years later.

Milei Takes On the Unions

Argentina’s Senate approved Milei’s “Ley de Modernización Laboral” by a 42-30 vote on February 12th after a 15-hour debate. This is the biggest change to Argentine labor law in decades. The bill now moves to the Chamber of Deputies, where the government believes it has over 129 votes to pass.

On February 11th, thousands of people clashed with police outside Congress. At least 71 were detained, and more than 15 were injured.

The reform is huge. It allows 12-hour workdays, stops expired union agreements from being automatically renewed, makes more jobs count as ‘essential services’ so that 75% of workers must keep working during strikes (including telecoms, aviation, ports, and education), limits severance pay to three times the average salary, and sets up a new fund paid for by employers to help workers. It also shifts wage talks from industry-wide deals to company-specific ones, making unions less powerful.

It is surprising that Milei has managed to do this in Argentina, a country with a long history of strong unions and Peronist influence. When you see images of the protests, remember these union workers have often supported Kirchnerism, the most left-leaning part of Peronism.

These protesters, even if they are sincerely opposing changes to their labor rights, are also pursuing an agenda to weaken Javier Milei. The same strategy was used against Mauricio Macri in 2018, and it proved effective. Street protests contributed to Macri’s downfall and helped pave the way for the Kirchnerists’ return to power in 2019.

Milei is aware of this. The real question is whether he can keep enough support to pass the bill in the lower house and withstand the strikes without giving in, as previous non-Peronist leaders did.

Mexico Discovers the Weekend

It’s an interesting contrast. Argentina, famous for its strong unions, is now passing reforms that weaken labor rights. Meanwhile, Mexico, with its own long history of workers’ movements, is only now beginning to discuss a 40-hour workweek.

On February 11, Mexico’s Senate voted unanimously to approve a constitutional reform that would reduce the standard workweek from 48 to 40 hours. The proposal now moves to the Chamber of Deputies, which is expected to vote on February 24 or 25.

The reform will roll out in stages: 46 hours in 2027, 44 in 2028, 42 in 2029, and finally 40 by 2030. It will affect 13.4 million workers. Important points include no pay cuts during the transition, electronic time-tracking starting January 2027, a 12-hour weekly overtime limit, and no overtime for minors. Workers will not have two required rest days until the 40-hour goal is met in 2030.

Mexico works more hours per employed person than almost any country in the world, at 2,226 hours per year, the highest in the OECD, and has had some of the least employee-friendly laws. This is great news for them, but it was about time.

From “Yankee Go Home” to “Welcome Back”

Last week, U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright visited Venezuela and announced investments totaling over $100 million to upgrade Chevron facilities. He told reporters the U.S. embargo on Venezuelan crude had “essentially ended,” and that production in some fields could double within 12 to 18 months. The first $500 million oil sale under U.S. supervision had already closed on January 14.

Wright is the highest-ranking U.S. official to visit Venezuela since Bill Richardson did so during the presidency of Bill Clinton.

Meanwhile, on February 12, thousands of Venezuelan students marched in the first major opposition protests since Nicolás Maduro’s capture. It was National Youth Day, and crowds gathered in Caracas, Bolívar, Táchira, and Carabobo, chanting, “Not one, not two—all of them.”

The students protested the stalled amnesty law and called for the release of over 600 political prisoners still detained. The Chavista National Assembly delayed the final vote on the amnesty bill because it is stuck on Article 7, which requires recipients to “submit themselves to the law.” The opposition sees this as an assumption of guilt.

It is striking that after 27 years of presenting themselves as the strongest opponents of U.S. influence and imperialism, Chavismo is now becoming the Trump administration’s most strategic partner in Latin America.

The irony is exquisite. The anti-imperialist revolutionaries are now taking orders from Washington, opening their oil sector to American companies with “preferential access,” and receiving the U.S. Energy Secretary like an honored guest. Twenty-seven years of rhetoric, gone in six weeks.

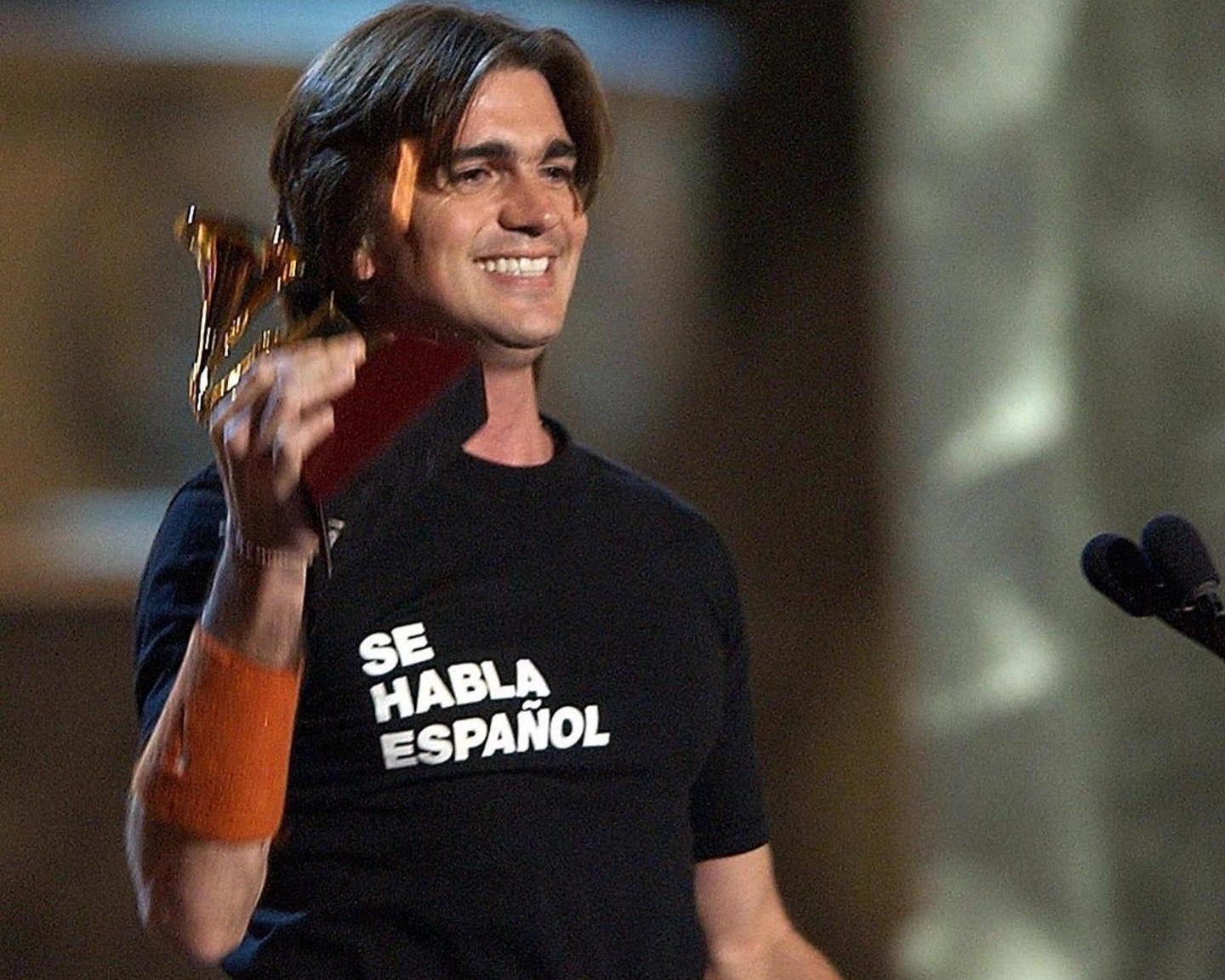

Juanes Did It in Spanish First

Decades before Bad Bunny was performing in Spanish at the Super Bowl, a Colombian artist had a #1 song in over 20 countries with “La Camisa Negra,” and this was Juanes.

Mi Sangre (2004) by Juanes was actually the first CD I ever bought. To be honest, it was a burned copy. His style even inspired me to grow my hair long for years.

Juan Esteban Aristizábal Vásquez was born in Medellín in 1972. Before his fame, he was a metal fan growing up in Medellín during the Escobar years, one of the city’s most violent times. At 15, he started Ekhymosis, a thrash metal band. When they broke up around 1998, he sold everything he owned to buy a plane ticket to Los Angeles.

There’s a lot of variation among his albums—rock, vallenato, cumbia—and he’s been doing a U.S. crossover in recent years. But his best work, for me, will always be his debut Fíjate Bien (2000). It has an interesting sound mixing rock with Colombian music and powerful protest lyrics. The title track, for example, addresses the landmine crisis in Colombia, a tragic legacy of guerrilla warfare and drug trafficking. (They took what you had / they stole your daily bread / they took you off your land / and it doesn’t end there ... Take a good look where you step / take a good look when you walk / lest a landmine / blows up your feet, my love.)

The song became an anthem—dark, personal, and urgent. That album won him three Latin Grammys in 2001.

He is also a committed activist. He founded the Mi Sangre Foundation to support landmine victims and co-founded “Paz Sin Fronteras,” which hosted massive concerts. In 2008, more than 300,000 people attended the Colombia-Venezuela border, and in 2009, over a million people came to the event in Havana.

He has won 29 Grammys, sold over 15 million records, and TIME named him one of the 100 Most Influential People.

That’s all for now. If you found this valuable, here’s how you can support me:

Subscribe for free to get editions like this every week: one main analytical piece, three important stories from Latin America, and one cultural recommendation to help you understand our region better.

Like this post by tapping the heart button. It helps more people discover LatAm Explained.

Leave a comment below. I read every single one, and your perspectives make my content better.

Share this with someone who’d appreciate my analysis of Latin America. Forward this email, or use the button below:

You can also follow me on Instagram, X, and TikTok for more of my content.

Gracias por leer. Hasta la semana que viene.