Even the President Isn’t Safe from Harassment

Claudia Sheinbaum’s assault exposed a truth every woman in Mexico already lives with.

Si quieres leer esta edición en tu idioma, suscríbete al canal de WhatsApp de LatAm Explained en español.

President Claudia Sheinbaum was walking through the historic center of Mexico City when a drunk man came up from behind, grabbed her by the waist, and tried to kiss her. The video is short and disturbing: you see her turn, push him away, and keep walking, surrounded by her aides. Within hours, she filed a criminal complaint and publicly called the incident what it was: harassment. Then she said the line that summarized everything: “If they do this to the president, imagine what they do to the rest of the women in this country.”

In Mexico, gender violence is so normalized that even the head of state can’t walk a few meters without being touched against her will. Sheinbaum’s reaction was strong but calm. She didn’t make a big scene or blame her security team. Instead, she did something that sent a message: she pressed charges. She turned something that happened to her into an example for everyone.

That action matters in a country where more than 70% of women say they have faced harassment in public. It also matters in politics. Sheinbaum’s simple security style, walking through crowds with almost no visible protection, has been one of her trademarks since she started the job, just as her predecessor López Obrador. It’s part of her effort to seem open and friendly, unlike some of the distant, heavily guarded presidents before her.

However, that same approach is now being questioned. Critics call it risky. Supporters say it is the cost of staying close to the people. Sheinbaum herself does not seem willing to stop: “We cannot isolate ourselves from society,” she said after the attack.

The opposition stayed quiet, not wanting to look like they supported her or made light of the attack. Their silence said more than any press release could. Violence against women is still one of the few issues Mexican politicians can’t use for their own gain without showing their own double standards.

In the end, showed that being a leader is not about acting like nothing can hurt you, but about facing what hurts everyone else.

All We’re Saying: Give Paz a Chance

Rodrigo Paz has officially taken office, ending nearly twenty years of Movement for Socialism rule and beginning a new chapter for Bolivia. His main message is clear: “capitalism for all.” However, he faces big challenges. The economy is struggling with 20% inflation, fuel shortages, and very little money left in national savings. Paz says he wants to focus on practical solutions instead of political theories, but his first day in office showed that politics still depends on strong symbols.

Among the foreign guests was Chile’s Gabriel Boric, a left-leaning president congratulating a right-leaning leader. This shows that Bolivia’s changes do not mean it will isolate itself from the world. Paz says he wants to restore normal relations with the U.S. and even work with the DEA, which would not have happened under Evo Morales or Luis Arce.

Socialists still hold significant power in Congress, and there is a real risk of protests or unrest. For now, though, people in Bolivia are giving Paz a chance. After twenty years of major changes, they seem ready to try a more balanced path.

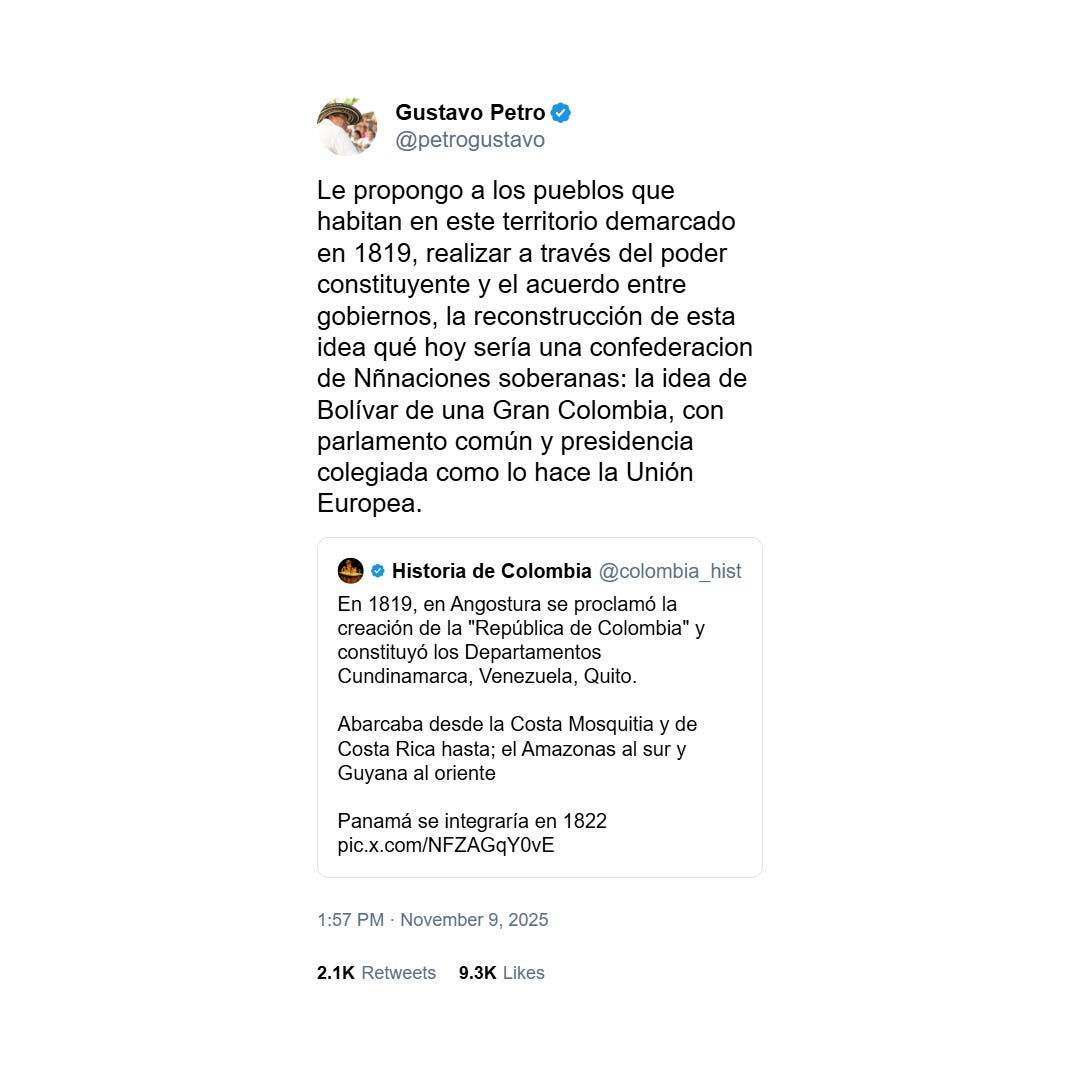

Petro’s Dream of a New Great Colombia

Colombian President Gustavo Petro has brought back one of Latin America’s oldest and boldest ideas: bringing together Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, and Panama again, just like Simón Bolívar did in the 1820s. Petro calls it a “confederation for the 21st century,” with shared citizenship, open borders, and even a digital common currency.

The original Gran Colombia collapsed in 1831, undone by distance, egos, and national ambitions. Two centuries later, the political divides are wider than ever. Venezuela is under dictatorial rule, Ecuador leans conservative, and Colombia itself is fractured.

The idea came up again in April during Daniel Noboa’s inauguration in Ecuador, and now Petro is talking about it again as he deals with a weak economy and dropping approval ratings. He says bringing countries together is the way to bring back “Bolívar’s legacy” and make the region stronger. Critics say it is just a way to avoid dealing with problems at home, a distraction that sounds nice but does not solve anything.

As a Venezuelan, I can say the thought of a reunited Gran Colombia feels powerful, almost romantic. But nostalgia isn’t politics. In today’s Latin America, Petro’s dream looks less like unity and more like wishful thinking.

The U.S. Deports a Victim of the Dictatorship It Condemns

In 2018, Yadira Córdoba lost her son when Nicaraguan police shot protesters during an uprising against Daniel Ortega’s regime. She fled to the United States to seek asylum, bringing evidence of her son’s killing and hoping to share her story in court. Last week, her request for help was denied, and she was told to leave for Honduras, where she has no family or legal status.

Her case caused outrage because it shows a clear contradiction. The U.S. government sanctions Ortega, supports opposition media, and calls Nicaragua a dictatorship, but is still deporting someone harmed by that regime. Congressman Joaquín Castro put it simply: “If we fail to protect Yadira Córdoba, America’s beacon of light will dim.”

That beacon has already dimmed. The U.S. cannot claim to defend democracy abroad while turning away people fleeing from oppression.

Nicaragua also deserves more attention. The government’s actions against its people are as severe as those in Cuba or Venezuela, but they receive less notice. Córdoba’s story is a reminder not to overlook them.

The Dominican Who Taught the World to Dance

Juan Luis Guerra just released a duet with Sting which feels both unexpected and completely right. The British rock legend sings “Estrellitas y Duendes” all in Spanish. His accent is soft and respectful, and his voice fits naturally with Guerra’s poetry.

This isn’t a gimmick or a crossover for show. It’s a tribute from one global musician to another, proving that some music speaks for itself, no translation needed.

For many of us, Guerra is more than an artist. He’s part of our childhood memories. At home, his CDs played often. Sunday mornings smelled like coffee and cleaning, adults danced merengue in the living room, and I learned that happiness has its own rhythm.

That’s why this collaboration is special: it honors someone who brought Dominican music to the world. Guerra blended merengue, bachata, and jazz to write songs about love, humor, and faith. “Ojalá que llueva café” turned hope for a better life into music. “Visa para un sueño” made the story of moving to a new country sound beautiful. Later, after becoming a Christian, he wrote “Las Avispas,” using only Bible verses, and turned it into a song people could dance to.

I mean it, when these verses play, you’re about to witness some serious moves on the dance floor. (I have an admired God in heaven / and the love of His Holy Spirit / by His grace I’m a new man / and my song overflows with joy.)

For decades, he has made people think while they dance. His music is elegant, deeply connected to his culture, and full of spirit and energy. I’ve always thought of him as one of the Caribbean’s great thinkers, like Rubén Blades—musicians who use their songs to tell stories.

Sting didn’t discover Guerra; he honored him. With this duet, the rest of the world finally gets to see what the Caribbean has always known: joy can be profound, and Juan Luis Guerra has shown this for decades.

I could write about Juan Luis Guerra for pages, but to keep it simple, I’ll just suggest you listen to his 2012 concert in Santo Domingo, where he plays most of his best songs.

That’s all for this week. If you liked what you read, please subscribe.

You’ll get something like this every Monday: one main analytical piece, three important stories from Latin America, and one media suggestion to help you learn more about our region.

You can also follow me on Instagram, X, and TikTok for more.

Gracias por leer. Hasta la semana que viene.