Nobody Knows What Happens Next in Venezuela

Here’s what I tell friends who ask me where Venezuela is heading.

Si quieres leer esta edición en tu idioma, suscríbete al canal de WhatsApp de LatAm Explained en español.

The last few days have been intense. I keep getting messages from friends, colleagues, and even people I haven’t heard from in years, all asking the same question: what will happen in Venezuela?

I take it as a compliment. It means a lot to me that people trust my judgment, or at least believe I follow the news and talk to enough people to understand what’s going on. But here’s the truth I keep telling everyone: if someone claims to know what’s next for Venezuela, they’re lying.

Our media is a big part of the problem. For at least the last ten years, the regime has, by design, made it impossible for Venezuelans to get reliable news, leaving a big gap (IPYS Venezuela calls this news deserts). That gap is now filled by old-school, outdated journalists, younger exiled journalists trying to earn a living by monetizing their content, analysts, influencers, consultants, former officials, and commentators with their own agendas. International media often relies on these same people, so much of what you see on English-language TV comes from sources whose motives aren’t always clear.

Take Juan González as an example. He’s a former Biden advisor who’s been in the news again this week. The Human Rights Foundation accused him of having conflicts of interest with creditors and lobbying against sanctions on Maduro, though he denies it.

Some critics say his connections control his opinions, while others think he’s being blamed unfairly. The main point is that when these people talk about Venezuela, none of them really speaks for Venezuelans.

Here’s what we do know: the United States is taking more action. The Cartel de los Soles, which I’m not sure is described accurately by Washington, is, as of today, officially considered a terrorist group by them. Warships with twelve thousand military personnel are now close to Venezuelan waters. This is real, not just talk.

Do most Venezuelans want foreign troops here? No. We care a lot about our country’s sovereignty, especially because it is already being violated thanks to Cuban, Russian, Chinese, Iranian, and Turkish influences, among others.

Do most Venezuelans want Maduro gone? Yes, and not just in theory. People have taken to the streets many times—in 2014, 2017, 2019, and 2024. They marched, protested, organized, and voted. The regime answered with violence, prison, torture, exile, and a total disregard for human life.

So when people ask why there’s an aircraft carrier off the coast or why Washington is now thinking about options that once seemed impossible, the answer is simple. Venezuelans have already tried everything they could. The regime just didn’t care.

One last thing: in 2024, Venezuelans voted and chose to remove Maduro. If the crisis ends with that result, Venezuelans have already made their decision at the polls. Machiavelli would say that the end justifies the means, and in realpolitik terms, that is true in this case.

Bolsonaro Still Acts Like the Rules Don’t Apply to Him

We’ve already discussed Bolsonaro’s conviction in this newsletter, the one that meant he would end up in prison eventually. This week just sped things up. He was supposed to be taken into custody, but when investigators found out he had used a soldering iron to tamper with his ankle monitor at midnight, the Supreme Court decided to arrest him sooner. This wasn’t just for show, but a direct response to an obvious escape attempt.

Judge Alexandre de Moraes ordered his arrest before trial after police learned Bolsonaro was considering hiding in embassies and that his supporters were preparing to stop police from reaching his house. This kind of behavior isn’t new. Bolsonaro has always acted as if he didn’t have to answer for what he did, whether it was encouraging people to break into government buildings or thinking about overturning Lula’s win.

Now he’s sitting in a federal police cell, and the irony is hard to miss. After years of denying reality, it’s finally the one thing he can’t get away from.

This Isn’t the Usual News We Read from Costa Rica

Rodrigo Chaves, Costa Rica’s president, came just four votes short of losing his immunity and facing trial. This is the first time a president in Costa Rica has ever reached this point, which shows how serious the accusations are.

The Assembly rejected the first case, which involved audio recordings where Chaves allegedly asked for “cariñitos,” or small payments, to reward a campaign financial supporter. The second case, still being reviewed, is even more unusual. It involves beligerancia, an electoral offense that means openly supporting a candidate when campaigning is not allowed. No president has ever done this so openly before.

Chaves responded by accusing the courts, the Tribunal Supremo de Elecciones, and Congress of planning a “left-wing coup” against him. In reality, he is the one trying to change how institutions work. He has openly pushed for a strong legislative bloc that would let him control Congress and eventually influence the courts. This is risky in any democracy, especially when the president is still very popular, even with ongoing investigations.

Costa Rica is the last place in the region where you’d expect to see democracy under threat. But if anyone could put that reputation at risk, it’s Chaves.

I want to thank my friend Alonso Martínez, who talked with me about this and provided more context. What he described is worrying.

Colombia Deserves Better Than This

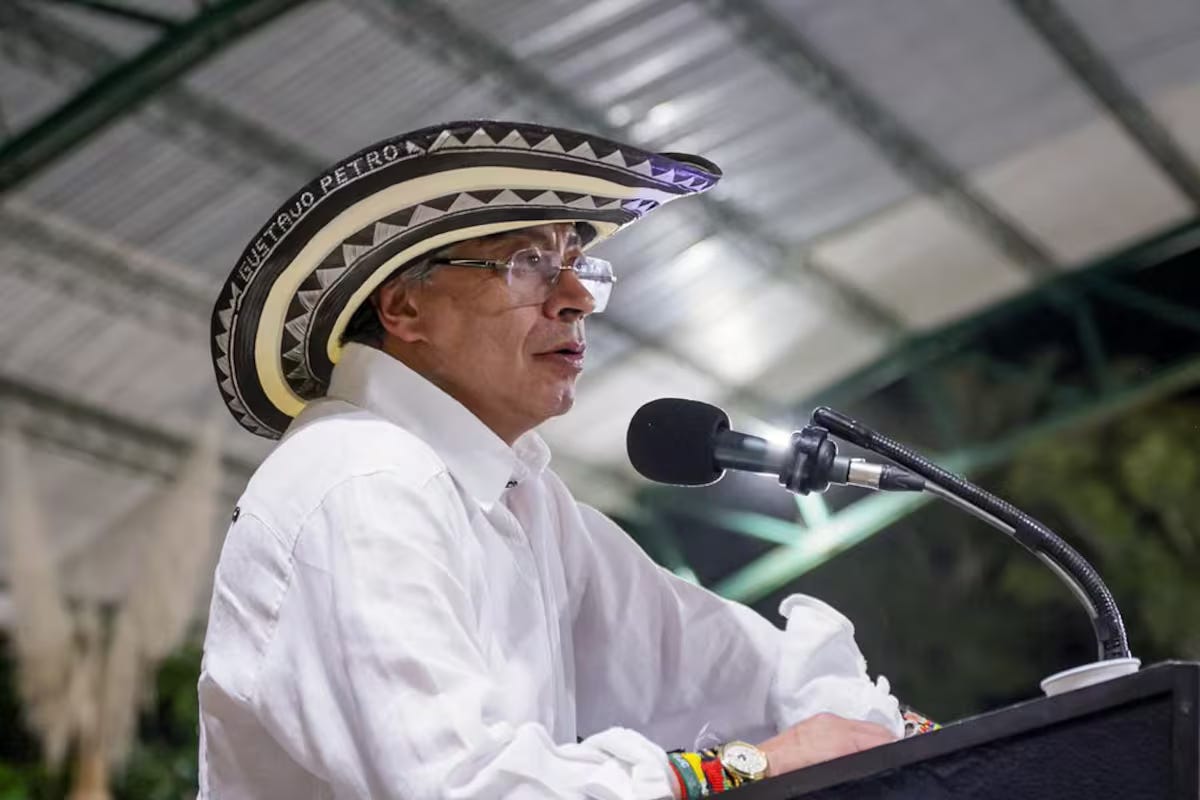

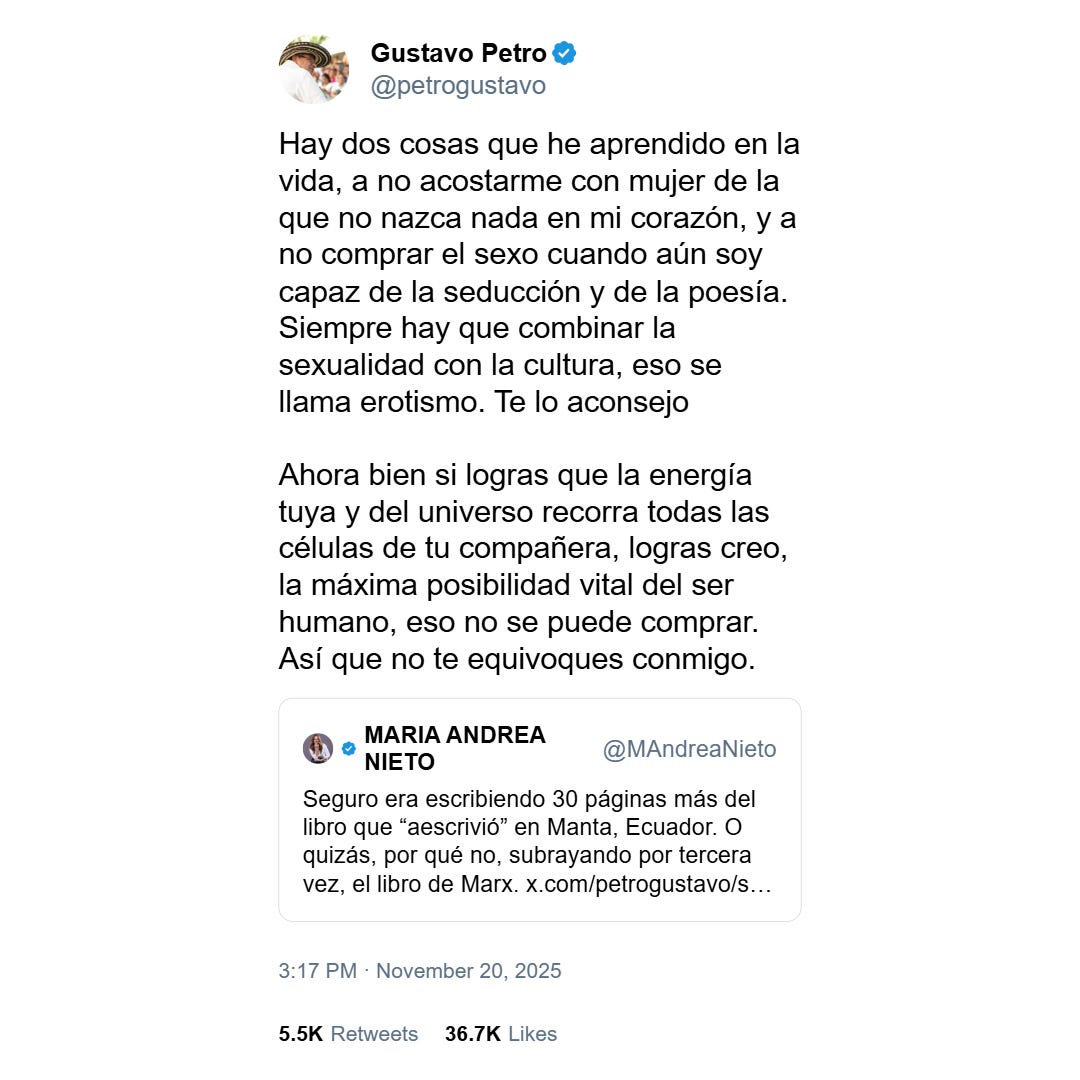

Gustavo Petro’s latest scandal isn’t really about money or legality. He shared his bank records to answer Trump’s claim that he’s connected to narcotrafficking, which is reasonable. But among the transactions was a €40 charge at a Lisbon strip club. Instead of addressing it seriously, he joked that he doesn’t need to pay for sex because he still has “seduction and poetry.”

Right now, Colombia is dealing with an economic slowdown, rising insecurity, and tense pre-election times. People are tired. They want seriousness, not jokes.

Authorities have already said there’s nothing illegal about the charge. The real issue is how embarrassing it is that Colombia’s president is once again making headlines for behavior that would shame any public official, let alone a president.

Colombians deserve a president who doesn’t turn himself into a joke every few weeks. This isn’t normal for a leader. It’s just one more scandal in a long list, and people have every right to be tired of it.

Spain’s Memory is More Relevant Than We Think

I’ve said it before, and it’s still true: if we want to really understand Latin American politics, we need to look at Spain too. The way Spanish society handles power, leaders, and institutions has influenced how politics work in our region. This week, as Spain marks 50 years since dictator Francisco Franco’s death, the country has spent several days thinking about the tyranny that shaped the twentieth century.

Franco ruled Spain for almost forty years, keeping a tight grip on the country, limiting freedoms, and building strong connections between the military and the Catholic Church. After his death, Spain didn’t instantly become a top democracy (it ranked 19th in the 2024 Democracy Index). Instead, the transition was a slow process between old officials, new leaders, and a country worn out by years of fear. This complicated story is important, especially for Latin Americans who often hear a simpler version of Spain as either a villain or a model.

Two recent cultural works explain this period better than any textbook. The podcast XRey tells the story of King Juan Carlos I, who Franco chose as his successor. Juan Carlos later helped end the regime, but eventually became infamous for his scandals.

The miniseries Anatomía de un Instante looks back at the 1981 coup attempt, following President Adolfo Suárez and how he and others stood firm during the storming of Congress.

These stories remind us that transitions are complicated, heroes aren’t perfect, and democracy depends on people choosing restraint instead of force. By seeing how Spain deals with its past, we can better understand our own history.

That’s all for this week. If you liked what you read, please subscribe.

You’ll get something like this every Monday: one main analytical piece, three important stories from Latin America, and one media suggestion to help you learn more about our region.

You can also follow me on Instagram, X, and TikTok for more.

Gracias por leer. Hasta la semana que viene.