Not So Fast: The EU–Mercosur Trade Deal Is On Hold

A European perspective on why the deal stalled again.

Si quieres leer esta edición en tu idioma, suscríbete al canal de WhatsApp de LatAm Explained en español.

Just when it seemed like the EU–Mercosur agreement was finally about to come to life, it stalled again. The European Parliament voted to send the deal’s legal framework to the European Court of Justice for review, a process that could take more than a year.

We’ve talked about this agreement many times in this newsletter. For a long time, I wasn’t sure it would ever move forward. A few weeks ago, I was surprised to see some progress. Now, it’s stuck again.

Until now, we’ve mostly viewed the EU–Mercosur deal from a Latin American perspective, which makes sense. But it’s also important to look at the European side. Why is there so much resistance in Europe? Who opposes the deal, and for what reasons? What does this tell us about how the European Union manages trade, politics, and national interests?

That’s why I invited my Italian colleague and dear friend Paolo Timossi to write a guest analysis for this edition. Paolo is a literature graduate from Sapienza Università di Roma and a student in the Erasmus Mundus Master’s program in Crisis and Conflict Journalism at City, St George’s University of London.

In the following section, he explains the current state of the agreement from the European perspective, and the motivations, pressures, and internal contradictions that might make it fail (or not).

What the EU-Mercosur deal means for Europe and why it’s now in standby

Guest analysis by Paolo Timossi

After nearly 25 years of talks, the European Commission and four South American countries—Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay—have finally agreed to sign the long-awaited trade deal between the EU and Mercosur. In addition to these four members, the bloc also includes Venezuela, whose membership has been suspended since 2016 for political reasons, while Colombia is currently negotiating its accession.

The agreement is expected to create a shared market of about 700 million people, making it the world's largest free-trade area. It is based on slowly removing tariffs on many types of goods. Over the next 15 years, Mercosur and EU countries are supposed to each remove more than 90% of these tariffs on goods from the other group. In theory, this should create big economic opportunities on both sides of the Atlantic.

From an EU perspective, the main winners would certainly be European industrial sectors. Exports are expected to increase notably in chemicals, plastics, rubber, metals, and machinery, benefiting Central European industries in particular and German manufacturers above all. European companies would also gain access to Mercosur countries’ public procurement markets, opening the door to large government-funded projects.

As with any trade deal, however, there are likely to be losers as well. In this perspective, European agriculture appears to be the most vulnerable sector. Many experts have warned that cheaper Mercosur food products could flood European markets, further pressuring EU farmers, who are already facing a long-standing structural crisis.

That’s the reason why an army of angry farmers and tractors has recently taken to the streets of Brussels to protest the Commission’s decision. And that’s also why, pressured from agricultural lobbies, and following a very narrow vote in the European Parliament, the agreement has now been sent to the European Court of Justice for review. A process that can take 12 to 18 months.

Once again, EU policymaking finds itself caught in a web of competing national interests, slowing down decision-making and complicating strategic choices. The Commission’s frustration becomes even more understandable when considering the deal’s geopolitical implications, which many observers see as even more significant than its economic outcomes.

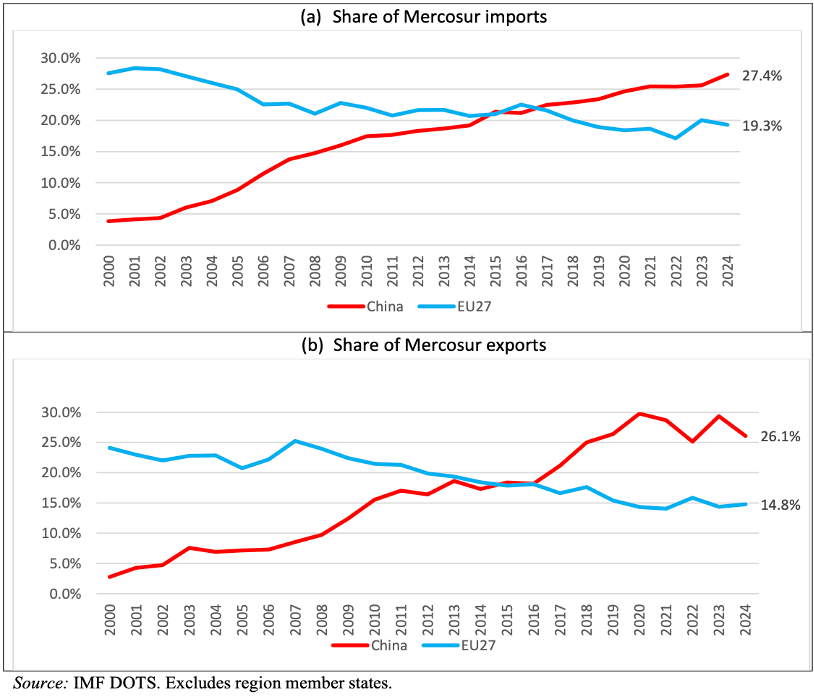

One of the agreement’s key objectives was to counterbalance China’s growing influence in Mercosur. Indeed, over the past two decades, China has overtaken the EU as the bloc’s leading trade partner, both in exports and imports. The deal was therefore meant to help Europe regain ground in Latin America.

More broadly, the agreement fits into the EU’s strategy to diversify its economic partnerships and reduce dependence on the United States. In this context, it may not be a coincidence that the deal was finalised amid the rise of the so-called “Donroe Doctrine”.

With the White House increasingly threatening both South American and European interests (and sovereignty), the Mercosur agreement could be read as a political response to Donald Trump’s provocations.

When the Mercosur-EU deal will eventually become effective remains uncertain, but the current situation already confirms a deeper, evergreen dilemma within the European Union: while trying to act as a global body (both economically and geopolitically), its fate is, once again, affected by short-term interests, internal divisions, and national political pressures. Although nothing new, yet always frustrating.

Peru: Another Impeachment Attempt

It had been months since Peruvians last tried to remove their president. Sooner or later, it was bound to happen again.

Interim President José Jerí, Peru’s eighth president in ten years, held secret meetings with a Chinese businessman in late December and early January. He did not record these meetings on his official agenda. When the media revealed these off-the-record encounters, Jerí apologized and called it “a mistake” to meet “hidden” without transparency. The Attorney General has started a preliminary investigation for alleged influence peddling.

Congress responded quickly. Six censure motions have been filed, using a new legal shortcut that requires only a simple majority to remove him instead of the usual two-thirds supermajority.

The most surprising and sad part is that many Peruvians would rather keep Jerí in power until the April elections. He still has 44% approval, which is very high by Peruvian standards. More than 100 prominent citizens published an open letter urging Congress not to remove him, saying the country needs “stability” before the elections.

That’s how normalized it is in Latin America, especially in Peru, for politicians to act irregularly. Jerí is the lesser evil simply because removing him would mean more chaos. The bar is underground.

Colombia and Ecuador: Trade War Over Drugs

On January 21, Ecuador’s President Daniel Noboa announced a 30% “security tariff” on all Colombian imports, saying Colombia was not helping enough to fight drug trafficking and illegal mining that drive violence in Ecuador. Colombia responded within a day by putting a 30% tariff on 20 Ecuadorian products and stopping electricity exports to Ecuador.

Noboa clearly wants to follow Trump’s approach. He has said this move is inspired by Trump’s use of trade penalties to push for policy changes. His concerns about Colombia are real, since Colombia is the world’s largest cocaine producer. More cooperation on border security could help Ecuador, which is facing record homicide rates from gang violence.

However, Ecuador has a large trade deficit with Colombia, importing $1.67 billion while exporting much less. A 30% tariff across the board will raise prices for Ecuadorian consumers and businesses on Colombian fuel, food, and manufactured goods. With this trade imbalance, the move may not benefit Ecuador’s economy. Noboa may appear tough on crime and align with Trump, but ordinary Ecuadorians will end up paying more.

Guatemala: Arévalo’s Nightmare First Two Years

On January 18, President Bernardo Arévalo declared a 30-day state of emergency after the Barrio 18 gang led prison riots and attacks that killed at least seven police officers. Inmates took 46 prison guards hostage in three prisons, demanding their leaders be moved back to lower-security facilities. Security forces freed all the hostages and recaptured gang leader Aldo “El Lobo” Dupie. Afterward, the gang carried out more attacks on police across Guatemala City.

Arévalo’s first two years in government have been extremely difficult. He won the 2023 election on an anti-corruption platform, but the old establishment tried many ways to stop him from taking office, including trying to nullify the election results and blocking his party’s registration. He finally became president in January 2024 after months of uncertainty and protests.

Now he faces another crisis. By the end of 2025, Guatemala’s homicide rate reached 16.1 per 100,000, which is more than double the global average. Gangs control entire neighborhoods, and the prison system is so corrupt that some imprisoned leaders had king-size beds, air conditioning, and restaurant food delivered to their cells. Arévalo is trying to reform a deeply flawed system, but gangs are responding with violence. Democracy in Guatemala is still under threat from many directions.

Brazilian Cinema’s Sweet Moment

People in Brazil are excited about the four Oscar nominations for “The Secret Agent,” and even more after “I’m Still Here” won Best International Feature last year. Brazilian cinema is enjoying a strong moment. Over a million Brazilians have watched “The Secret Agent” in theaters, which stands out since fewer people are going to the movies these days. President Lula said it shows that Brazil can share stories with the world.

So the obvious recommendation is “The Secret Agent,” a film about a widowed father who is persecuted by Brazil’s military dictatorship in the late 1970s. Wagner Moura, who you might know as Pablo Escobar from Netflix’s “Narcos,” was nominated for Best Actor. He is the first Brazilian ever nominated in a lead acting category.

But it’s also worth checking out other films by Kleber Mendonça Filho. “Aquarius” (2016) stars Sônia Braga as a woman standing up to construction developers in Recife. “Bacurau” (2019) is a near-future thriller about a rural village fighting off foreign mercenaries, and it won the Jury Prize at Cannes.

Mendonça Filho is known for making political films, and it’s no accident that these two acclaimed Brazilian movies are set during the dictatorship years. Brazil is confronting its difficult history through film, using stories to reflect on authoritarianism at a time when these warnings matter again, and the world is watching.

That’s all for this week. If you liked what you read, please subscribe.

You’ll get something like this every Monday: one main analytical piece, three important stories from Latin America, and one cultural suggestion to help you learn more about our region.

Gracias por leer. Hasta la semana que viene.