Venezuela After Maduro: A Transition to What?

The fall of a dictator, not the fall of a regime.

Si quieres leer esta edición en tu idioma, suscríbete al canal de WhatsApp de LatAm Explained en español.

I spent the holidays in Spain, catching up with friends and family and staying out too late on New Year’s Eve. On January 2, still recovering, I decided to stay in. During the day, I sent out the last issue of this newsletter, and that night I binge-watched The Sopranos until nearly 5 in the morning.

At about 7:05 a.m., my phone started ringing. My best friend in Caracas kept calling, but I missed the calls. When I checked WhatsApp, I saw messages from him and videos flooding my Venezuelan group chats: bombings in Caracas, at La Carlota airbase, Fort Tiuna, La Guaira, and Higuerote. At first, I thought it was a military uprising from inside Venezuela. But a few minutes later, I saw OSINT experts on X analyzing the helicopters in the videos, saying they matched the ones the United States had at its base in Puerto Rico. That’s when I realized the U.S. was invading Venezuela. I hadn’t slept that night, and I wouldn’t get much sleep in the days that followed.

In case you haven’t followed the news—though if you’re reading this, you probably have—U.S. troops entered Venezuela early on January 3rd, bombed specific military sites, captured Nicolás Maduro and Cilia Flores, and took them to the United States to face justice in New York. At least 150 aircraft took part in the operation. 77 military personnel died, including 32 Cuban intelligence and military officers who were guarding Maduro. Tell me about foreign intervention. Two civilians were killed in the strikes. The destruction was little and limited to specific areas, and while some people lost their homes, the operation was surprisingly precise. No one expected that if the U.S. bombed Venezuela, it would be so painless, at least in relative terms. Please read my words carefully here.

January 3rd was very confusing because there was a power vacuum. Defense Minister Vladimir Padrino López and Interior Minister Diosdado Cabello spoke early that morning, saying they were out in the streets with military and police forces. There were rumors, even confirmed by some international outlets, that Vice President Delcy Rodríguez was in Russia, and National Assembly President Jorge Rodríguez did not appear for hours. Venezuelans were excited about Maduro’s capture, but no one knew who was actually in charge. People couldn’t go out to celebrate as Venezuelans did abroad in Miami, Buenos Aires, Madrid, and other cities.

Then Donald Trump held a press conference in Florida. He said they didn’t think María Corina Machado had enough respect to lead the country and that they would work with Vice President Delcy Rodríguez. Since then, what has really surprised me is how united Chavismo has been. I always thought that if the U.S. invaded, which I considered possible, Chavistas would escape and try to find exile somewhere safe. But that hasn’t happened. They are still there, resisting in their own way, following U.S. policies but working together. They’re staying put.

In just over two weeks, we’ve seen major changes that no one could have predicted. PDVSA, our oil company, announced it would give oil to the U.S. after Trump said they would take it. The CIA director visited Caracas and met with Delcy Rodríguez. They have started releasing political prisoners, but it’s happening very slowly. I want to point out that Venezuela has between 800 and 1,200 political prisoners, and fewer than 200 have been released so far, including some journalists, but not nearly enough.

So when people ask me what’s happening in Venezuela and what’s going on right now, this is my answer: We’re in a transition, but we don’t know where it will lead.

Chavistas have always been good at buying time and stalling, and it’s worked for them many times. Now, it seems they’re trying to follow U.S. demands in public, at least on the surface, to stay in power with as little damage as possible. In reality, Chavismo is still intact except for Maduro and Cilia Flores, who are now in prison. The real concern is that Chavistas could secure their position and stay in power by meeting some U.S. demands, but then U.S. attention might shift elsewhere, letting Chavistas remain in control for years, just as they have for the past 27 years.

However, there are signs that U.S. interests are long-term. A few days after the attack, Trump met at the White House with oil executives from 17 companies, including Chevron, ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips, and Shell, and invited them to invest in Venezuela. The oil executives were skeptical. Most who spoke publicly that day said Venezuela still isn’t stable enough, mainly because Chavismo is still in power. This is the same regime that seized and expropriated their assets several times before. For U.S. oil interests, a democratic transition will eventually be necessary. The instability that makes Chavistas acceptable partners now will eventually become a problem for investors who need guarantees.

There’s another factor: the U.S. forcing Chavistas to make these concessions is disappointing their own supporters. I haven’t been able to talk to many Chavistas since I’m not there, and people are afraid to speak to the international media. But if you look, for example, at the comments online about PDVSA’s announcement to give oil to the U.S., Chavistas aren’t happy either. They now make up less than 20 percent of the population, but if Chavismo wants to stay relevant, it needs its loyalists. Watching your government hand over the country’s oil wealth to the “empire” you’ve spent 27 years criticizing is not what Chavista supporters expected.

So I’m cautiously optimistic about Venezuela’s future right now. The contradictions are adding up. Trump wants stable oil for U.S. companies, which will eventually require democracy. Chavistas need to survive, so they need U.S. tolerance. The opposition wants power, which depends on both. Something will have to change.

I’m sorry I haven’t sent out the newsletter in the past two weeks. I’ve been busy reporting on daily developments, making short-form content mostly for Instagram, and giving interviews to other outlets. I also wanted the events to unfold until we had enough clarity to analyze. Thank you for sticking with me. Thank you for reading. And thank you to the subscribers who reached out and asked about my friend and family back home; it meant the world to me.

This edition is only about Venezuela, but we’ll have another one this week covering other news in the region.

Who Is Delcy Rodríguez?

Before January 3rd, most people had never heard of Delcy Rodríguez. After that date, international media, especially The New York Times, began describing her as a technocrat and pragmatic moderate. This view is off the mark. Both she and her brother Jorge Rodríguez are hardline Chavistas, and she has always shown an unapologetic approach in her career.

Journalist Ibéyise Pacheco has reported that Rodríguez once had a falling out with Hugo Chávez and insulted him during a diplomatic trip to Russia. This incident is said to be the reason she was not a key figure during Chávez’s last years. She only became prominent again when Maduro took office in 2013.

There is no doubt she is smart. She spent years representing Venezuela internationally, first as Foreign Minister and then as Vice President, where she managed Chavismo’s global alliances. She knows how to appear as a moderate technocrat when it suits her, and it seems the White House and Trump believe this image. However, she is actually a committed. Any reforms or concessions she makes are not based on her personal beliefs but are part of Chavismo’s strategy to survive, similar to the economic changes Maduro made in the late 2010s to face hyperinflation.

When Rodríguez was Vice President, she was in charge of SEBIN, Venezuela’s political police. This role made her directly responsible for the repression and torture many Venezuelans have experienced.

The legal process used to swear her in as interim president, called “forced absence of the president,” is not found in our Constitution. The Supreme Court, controlled by Chavistas, simply created it.

It is hard to say exactly what Chavistas want in the near or distant future. However, it seems likely they hope to put Rodríguez forward as a candidate in a future presidential election. She is their strongest option for keeping their movement going, and Trump is helping give her the legitimacy she needs—although this could backfire.

What Venezuelans Really Think

The first thing I want to point out is the enormous civility and dignity Venezuelans showed during the U.S. attacks. There were no riots, no violence, no outbursts. What were people doing? They went to supermarkets and lined up to buy food. They went to gas stations to supply gas. They organized themselves to buy U.S. dollars for the uncertainty ahead.

My sister María Verónica calls this the moral reserve of Venezuelans, and I saw it clearly that day.

Take the recent Economist poll from January 13th. Even though The Economist isn’t known for supporting Trump, the poll found that only 13 percent of Venezuelans opposed Maduro’s capture. That tells you how desperate people are for change after years under Chavismo. Nearly 80 percent now believe the country’s political situation will improve in the next year, and about 70 percent think their family’s economic situation will get better too.

People are most divided on who should lead the country. Still, almost half believe the U.S. should have a role in Venezuela’s government. More than a third think the Venezuelan government should control the oil industry. Nearly 70 percent want new presidential elections, and almost 70 percent want those elections within six months.

María Corina Machado remains the most popular leader, with almost 50 percent of people saying they would vote for her. Delcy Rodríguez has only 2.5 percent. Edmundo González gets almost 10 percent, so together with Machado, about six out of ten Venezuelans support the opposition.

One surprising fact is that Donald Trump and Marco Rubio have the highest approval ratings among political leaders in Venezuela. Both are viewed more favorably than Machado and González.

To people asking me if there are still Maduro supporters demanding his release: Did you ever watch the movie Good Bye, Lenin? That woman was still supporting the socialists until the very end.

Yes, there are some Chavistas still, but the vast majority of Venezuelans are happy Maduro is gone.

Machado’s Meeting with Trump

If Chavistas have been on a rollercoaster these past two weeks, the opposition has too. On January 3rd, during those confusing hours, the opposition stayed quiet until late in the day. When Trump said Machado couldn’t lead because she lacked the people’s respect, it hit hard. It took the opposition days to bounce back.

This is especially funny for people who claimed Machado was a puppet of U.S. interests. It turns out that anti-Trump views from Machado’s team in the past, along with Edmundo González’s meeting with President Biden at the White House, affected Trump’s perception. Remember, Trump was Juan Guaidó’s main ally when he claimed the presidency in 2019. He’s long been disappointed by the Venezuelan opposition.

We were happy when Machado won the Nobel Peace Prize because it meant the world recognized how much Venezuelans have suffered and fought. Still, for most of us, the prize doesn’t matter nearly as much as finally getting our democracy and freedom back.

Machado is not the typical Western political figure that you can scrutinize for every action. She’s a leader, a single-unit political force who has worked for decades to oppose the brutal Chavismo dictatorship. This woman has faced hardships in her personal life. So we see Machado’s words about Trump not as something she truly believes, but as someone doing everything in her power to get the opposition representation in this transition.

It looks like she pulled it off. Reports say that after their meeting, Trump gave her his phone number directly. I don’t think Edmundo González will end up taking office, and that might be better for him in the long run. If Venezuela heads toward open and free elections, with U.S. oversight and pressure on Chavismo, Machado will likely become the next president. That’s what people want.

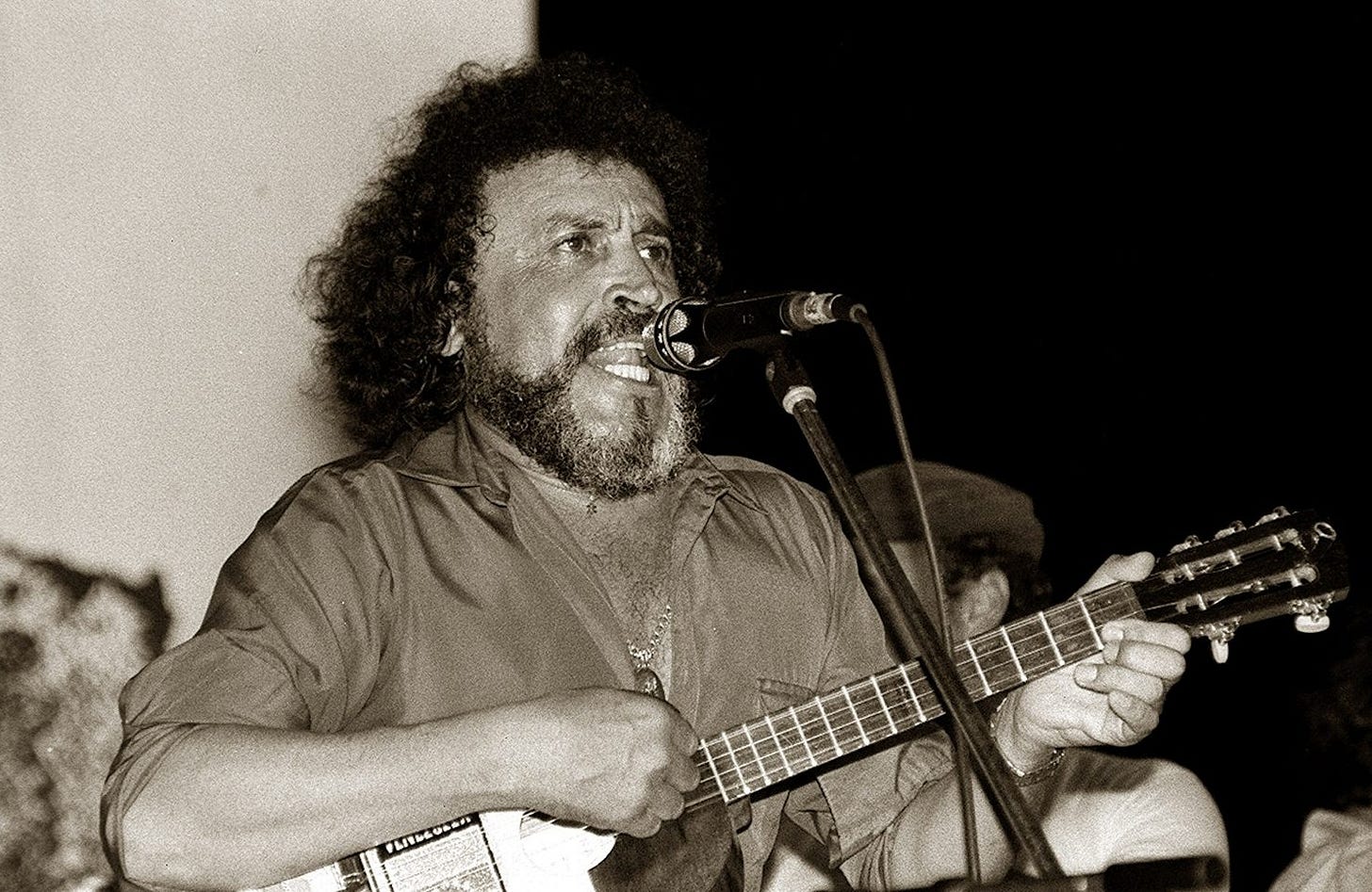

The Music of Alí Primera

Over the past few weeks, I’ve seen many left-wing activists outside Venezuela condemning the U.S. military buildup in the Caribbean and the attack on Venezuelan soil. Almost all of them rely on the same cliché cultural references.

They don’t know the Venezuelan context. None of them mentions Alí Primera.

Alí Primera was one of Venezuela’s most important folk singers in the twentieth century. His songs were openly anti-imperialist, focused on social issues, and always defended the poor. With his beautiful voice, he sang about hunger, inequality, and oil long before Chávez, Maduro, or the Venezuela we know today.

I’ve always found his work fascinating, and I find tragic how Chavismo took over his legacy. First Chávez, then Maduro, used Primera’s music while leading in ways that made his lyrics feel painfully relevant again. The poverty he described in “Techos de cartón” is even worse today than it was over forty years ago.

Alí Primera died in a car accident in 1985. He had received threats from security forces, so many people questioned how he died. Still, there’s no doubt about his importance. He is still one of the clearest moral voices Venezuela has ever had.

My favorite song is “Ahora que el petróleo es nuestro,” which Primera wrote after oil was nationalized under President Carlos Andrés Pérez. (Now that the oil is ours / long live sovereignty / so tell me, Mr. President / what if it were turned into food? / I don’t say this out of obsession / or because I feel like it / but the people, my friend / are sovereignly hungry.)

It’s hard to read those lines without seeing the main contradiction in Venezuela today.

That’s all for this week. If you liked what you read, please subscribe.

You’ll get something like this every Monday: one main analytical piece, three important stories from Latin America, and one cultural suggestion to help you learn more about our region.

Gracias por leer. Hasta la semana que viene.